Part One: Introduction

Thelema includes both monistic and dualistic doctrines, and Crowley makes monistic and dualistic pronouncements throughout his writings.

For our purposes, monism will mean any theory or doctrine that in some sense denies the existence of a distinction or duality in some sphere, either in fact or in thought.

An example of one of Crowley’s monistic pronouncements can be found in Liber DXXXVI.

The Universe is one, omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent. Its substance is homogeneous, and the substance cannot be said to possess the qualities of Being, Consciousness and Bliss, for these are rather the shadows of it, which are apprehended by the highly illuminated mind when it comes near thereto. Time and space themselves are but illusions which condition under veils.

Liber DXXXVI, Ch V, Sec 1

In general Crowley describes the Thelemic path of spiritual liberation in monistic terms, as a transcending of duality.

[…]Love is the enkindling in ecstacy of Two that will to become One. It is thus an Universal formula of High Magick. For see now how all things, being in sorrow caused by dividuality, must of necessity will Oneness as their medicine. Liber CL, Section II: Of Love

Dualism on the other hand shall mean any division of something—either in thought or in fact—into two opposed or contrasted aspects.

A prominent example of dualism in Thelema can be found in its foundational text, Liber AL vel Legis (AL).

I am Heaven, and there is no other God than me, and my lord Hadit.

AL I.21

This statement assumes there are two fundamental divine principles, not just one.

There are also numerous pluralistic statements throughout Crowley’s writings. For our purposes pluralism will mean any condition or system in which two or more states, groups, principles, sources of authority, etc., coexist. Any statement in support of pluralism, therefore, is by definition a statement in support of dualism.

Any of Crowley’s numerous statements in support of a multiplicity of unique, irreducible individuals is pluralistic (and hence dualistic) in the sense just described.

[E]ach ‘star’ is the Centre of the Universe to itself […] Therefore you have an infinite number of gods, individual and equal though diverse, each one supreme and utterly indestructible […] If we presuppose many elements, their interplay is natural. It is no objection to this theory to ask who made the elements—the elements are at least there; and God, when you look for him, is not there. New Comment on AL I.3

On the one hand, Thelema is unabashedly individualistic. Crowley defined the Thelemic Age—the New Æon of Horus—as one in which “the individual [is] the unit of society.” The individual requires no social, political, or religious contextualization but is instead absolutely self-justifying. “There is no god but man.”

On the other hand, the Thelemic understanding of the universe unambiguously denies duality, and the Thelemic path of liberation necessarily includes transcending the illusion of duality.

The purpose of this essay—which will be published in multiple parts—is to resolve these apparent contradictions by showing how Crowley incorporated dualistic and non-dualistic or monistic truths into a coherent account of the universe and the individual’s relationship to it.

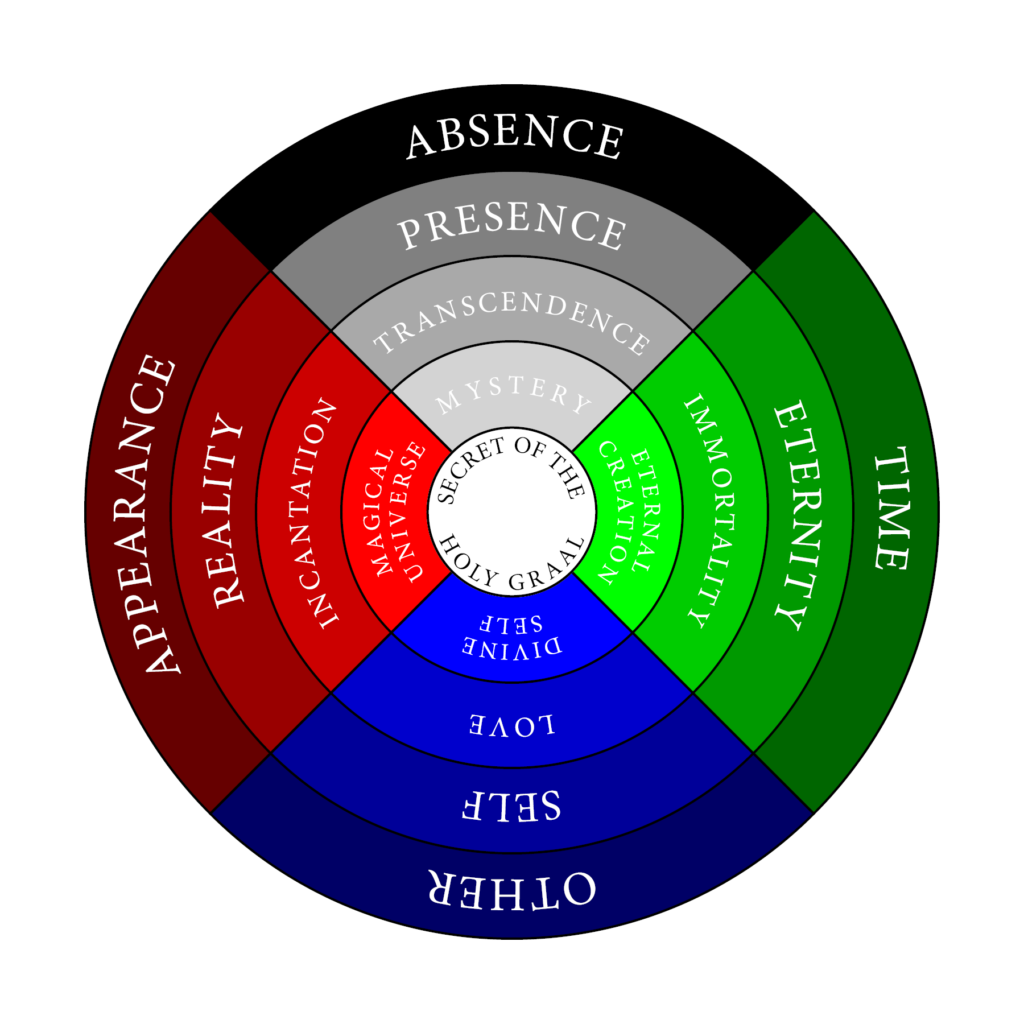

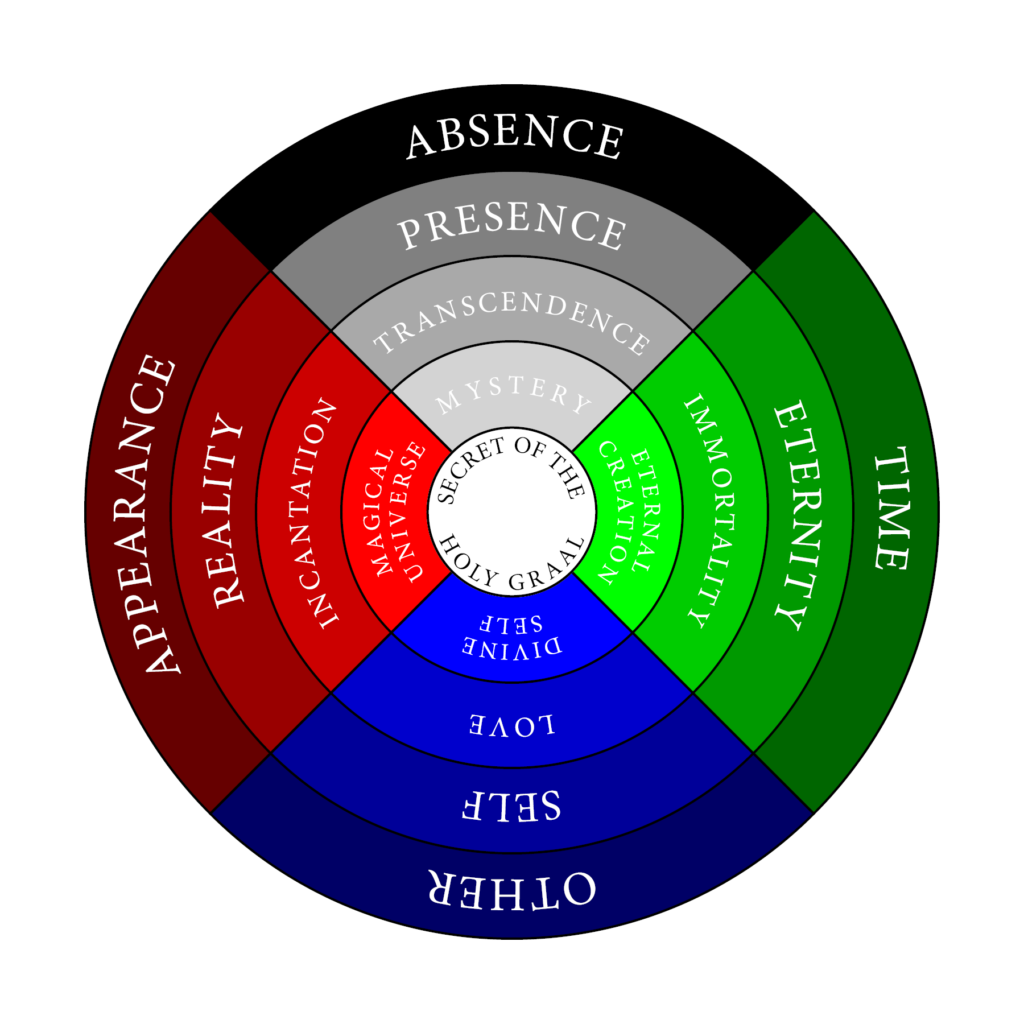

I will begin by providing a conceptual framework for more precisely discussing monism and dualism. I will then apply that framework to four distinctions:

- The distinction between Nuit and Hadit.

- The distinction between Nuit, Hadit, and the Star.

- The distinction between the Khabs and the Khu of any Star.

- The distinction between Stars.

In each instance we will analyze the precise manner in which parts or individuals are related or separated, and which relationships might be considered monistic and in what way(s). This will help make sense of Crowley’s seemingly contradictory statements about monism and dualism by incorporating those statements into a coherent account.