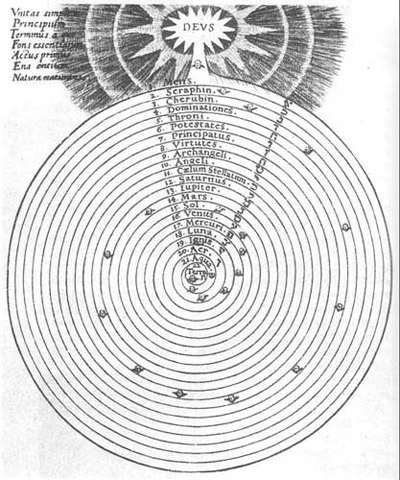

As mentioned previously, Crowley’s philosophy can be understood as a form of derivation monism: the requirement that the a priori conditions of experience must be somehow derived from a single, absolute first principle. For Crowley, the a priori conditions of experience are the subjective point of view (which he calls Hadit) and the intersubjectively accessible spatiotemporal universe (which he calls Nuit). The single, absolute first principle grounding these conditions he calls Qabalistic Zero or nothingness extended in no categories.

Additionally, Crowley can also be understood as being committed to a modified version of derivation monism called holistic monism. Holistic monism may be divided into two requirements. The holistic requirement is that empirical items must be such that all their properties are determinable only within the context of a totality composed of other items and their properties. As Crowley says, all of our empirical knowledge is “relative” or conditioned—or as Crowley sometimes puts it, “illusory”.

The monistic requirement is that the absolute first principle must be immanent within the aforementioned totality as its principle of unity. Crowley expresses this a number of ways. All manifestation (or what Crowley calls duality) “cancels out” or “balances”. The universe is apparently in ceaseless motion, and yet this motion adds to 0 or stillness. Hence, manifestions is identical with nullity, or 0 = 2.

Holistic monism can be viewed as a response to a problem originating in Platonic metaphysics, namely, how the first principle relates to or “participates in” the items it grounds. In order for the first principle to serve as ground, it must be divided up somehow into the things that it grounds. But then it loses its unity. But in order for it to maintain its unity, it has to transcend reality, and hence not have contact with it.

The holistic monist response to this problem is to maintain that the sum total of reality is one and is identical with the absolute first principle, but this does not mean that the first principle loses its transcendence, because reality itself is self-transcending. In other words, reality is constantly canceling or negating itself.

To put it another way, what the Neoplatonists said of the One—that it is self-transcending—holistic monists say of the sum total of reality itself. Reality must not be understood as an inert, static, unmoved substance but rather something more like a living being that is constantly producing itself through self-cancellation.

To model one’s individual life on the basis of nature, therefore, means to be in a state of continually overcoming one’s own sense of self, or more exactly, the sense that one has of being a separate, static substance standing apart from the rest of reality. This isn’t done through the denial of self, as in ascetic spiritual practice, but rather through the expansion of one’s sense of self through the affirmation and acceptance of more and more of the universe.

The Adept must accept every “spirit”, every “spell”, every “scourge”, as part of his environment, and make them all “subject to” himself; that is, consider them as contributory causes of himself. They have made him what he is. They correspond exactly to his own faculties. They are all – ultimately – of equal importance. The fact that he is what he is proves that each item is equilibrated. The impact of each new impression affects the entire system in due measure. He must therefore realize that every event is subject to him. It occurs because he had need of it. Iron rusts because the molecules demand oxygen for the satisfaction of their tendencies. They do not crave hydrogen; therefore combination with that gas is an event which does not happen. All experiences contribute to make us complete in ourselves. We feel ourselves subject to them so long as we fail to recognise this; when we do, we perceive that they are subject to us. And whenever we strive to evade an experience, whatever it may be, we thereby do wrong to ourselves. We thwart our own tendencies. To live is to change; and to oppose change is to revolt against the law which we have enacted to govern our lives. To resent destiny is thus to abdicate our sovereignty, and to invoke death. Indeed, we have decreed the doom of death for every breach of the law of Life. And every failure to incorporate any impression starves that particular faculty which stood in need of it.

Liber Samekh

From a macrocosmic point of view, the universe is “nothing” through and through. What we call “reality” is purely relative and illusory, and anything we say of it is, at best, only provisionally true. This reality does have an ultimate cause or first principle, but that principle is also nothing (the Qabalistic Zero). Both the self as experiencer and the object as experienced are particularizations or self-limitations of nothingness. The metaphysics is nihilistic through and through.

However, the self is a negative actuality expressed against the negativity of (apparent) reality. It expresses its negativity through the destruction of difference between itself and those things around it. Hadit unites continually and endlessly with Nuit. He is never substantial or separate—never a being possessed of a will but rather willing itself—always only ever overcoming the difference between himself and Nuit. This continual annulment of distinction Crowley calls love. It is a destruction, cancellation, negation, or overcoming which is productive of union.

The main mode of operation of the will is negative. It annuls distinction. But to annul distinction is to produce or to create something new, i.e., every “fresh new experience”. The nihilism or nothingness of reality is the condition of operation of the will. It allows the will to be unrestricted by any external being, and it sets the stage for the cancellation of nothingness, a negation of negation which produces a positive, affirmative reality.

Therefore the nihilistic metaphysics of the world can be viewed as the negative image from which an affirmative, positive view of reality can be constructed, i.e., willed. At the center of this positive, inverted image of the macrocosm is the magician who creates by destroying distinction between his or herself and the universe. The main method by which distinction is destroyed is through the unconditional, absolute acceptance of what is, as it is, or what I have elsewhere referred to as erotic destruction or erotic liberation.