In my opinion what makes Thelema distinctive is not the occultism, not the ontology, not the ethics, not the individualism. It’s that he took the western occult tradition with its God as a creative artist and inflected it through a Nietzschean understanding of life.

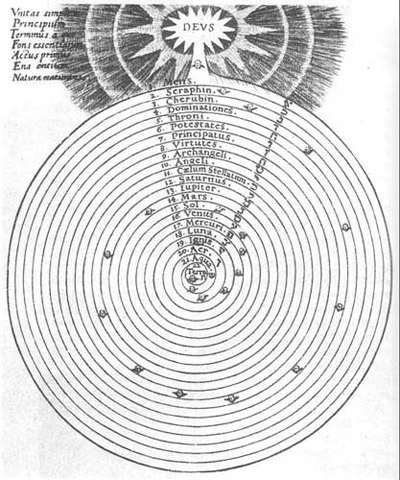

Renaissance occultism is based upon a view of the cosmos where everything is ordered into spheres or levels with Earth as the focus. Natural magic is about drawing power or spiritus down from higher spheres into lower ones. “Cabalistic” magic is about ascending to superluminary spheres and mastering the angelic forces there—which tips over very easily into mysticism, as it does in Thelema. In short it’s based on a hierarchical, anthropocentric view of the universe as a kind of container focused on human affairs, and the container is overall not that large.

This view was largely replaced by the natural philosophy in the 17th and 18th centuries. According to this new view, the universe does not behave according to purposes but rather mechanisms. There are no “pulls” in the universe, only “pushes”. And the universe in which these abstract mathematical laws operate is vast enough to overwhelm the imagination and the human perspective all together. The picture of the universe generated by this natural philosophy ultimately left up in the air the place of humans in it. And with this disenchanted view of nature came a challenge to both religion and magic.

Rather than recoiling from this picture of nature into a kind of reenchanted fantasy about life, Crowley instead embraces it. The sheer enormity of the cosmos is one of the premises of Crowley’s view of reality, embodied in the goddess Nuit. The pure mathematical view of reality is not rejected either but embraced. Mathematics was part of occultism going back at least to Pico, but Crowley really makes it one of the main themes of his spirituality. So in other words rather than trying to hide from the implications of modernism, Crowley leans into them.

And he understands the fundamental spiritual problem in a very modernist way. The problem we face is not suffering, and it’s not ethics. These are pre-modern or early modern ways of looking at the problem. No, the main problem is meaning. It’s the senselessness of the world. Crowley was motivated by this experience of senselessness at least since he was a student at Cambridge, and he writes about it at least as late as Little Essays Toward Truth.

What then determines Tiphareth, the Human Will, to aspire to comprehend Neschamah, to submit itself to the divine Will of Chiah?

Aleister Crowley, Little Essays toward Truth, “Man”

Nothing but the realisation, born sooner or later of agonising experience, that its whole relation through Ruach and Nephesch with Matter, i.e., with the Universe, is, and must be, only painful. The senselessness of the whole procedure sickens it. It begins to seek for some menstruum in which the Universe may become intelligible, useful and enjoyable. In Qabalistic language, it aspires to Neschamah.

The way he understands a possible solution to senselessness is very modernist as well. The solution cannot be sought in reason. Reason operates according to the principle of sufficient reason, i.e., for any proposition F, there must be a ground G for it, or for any event B, there must be a sufficient explanation A. Putting the principle of sufficient reason at the center of human relating to the world is what generated the picture of a senseless, purely mechanical world in the first place. Therefore, reason—specifically the application of the principle of sufficient reason—must be limited, but to limit reason it must be transcended.

But—the transcendence of reason cannot interfere with the legitimate operation of reason within its own domain. Crowley is not looking to reenchant nature in some naive way. He accepts the findings of the scientific view of reality and even holds them to be axiomatic for his spirituality. Nor can the transcendence of reason be a mere animalistic “overcoming” of reason. One cannot simply will oneself to be irrational, for instance. Both of these avenues would represent a kind of fanaticism.

So Crowley has to manuever somehow between the Scylla of rationalism on the one hand and the Charybdis of dogmatism or fanaticism on the other.

This is a very modernist—specifically German Idealist—way of looking at things. When a person with a background in the philosophy of Kant, Fichte, Hegel, and Nietzsche hears Crowley talking about transcending “because,” they’re hearing a tune they could hum in their sleep.

And Crowley’s proposed solution to this problem is will. Will transcends reason. You cannot ask “why” of will. In and of itself it prevents the questioning but instead gives orders. It’s authoritative. This is how he avoids rationalism.

But will also represents the “true” self of the individual. It is not a mere replacement for Jehovah. It is not a projection of the law of the father. Nor is it exactly bodily or animal instinct. This is how Crowley avoids fanaticism.