A religious rite ought to form a religious community around a common ethos: a set of commonly held values that are both cause and effect of the commonly recognized highest power.

Space-time, consciousness, and magick

Crowley was aware of the most cutting edge science of his time and correctly understood its implications for philosophy of mind.

The Magick of Baphomet

The understanding of the Law of Thelema with its demands and rewards gives one the best possible chance to make the most of a human life.

Am I turning magic into philosophy?

My work is a critique of an already existing but unacknowledged dogmatic philosophy.

Apophatic Theology and the Gnostic Mass

Deep calls to deep in the roar of your waterfalls; all your waves and breakers have swept over me.

Approaching Thelemic Magick

It’s hard to understand what Thelemic magick is if you begin from the premise that it is a subset or sub-genre of ceremonial magick.

For one thing, it makes it hard to understand what the Thelemic part of Thelemic magick is supposed to be. Is it just ceremonial magick in the Golden Dawn style but with different godnames used? I was badly pronouncing Hebrew at the walls before; now I’m badly pronouncing Greek. What difference should that make?

That leads to the idea that doing Thelemic magick just means adding Nuit, Hadit, Ra-Hoor-Khuit, etc., to the retinue of deities one practices with. It accommodates Thelemic magick to contemporary paganism.

Is Thelemic magick just ceremonial magick or Egyptian-flavored paganism but somehow … willing it more? Like I was a practicing occultist before, but somehow I wasn’t choosing to do it or wasn’t enthusiastic enough about it?

Or is it doing magick or devotion, but while doing these practices, I add the idea that I’m a god? I’m doing my LBRP as I was before, but in the middle of it I’m stopping to think, “I’m such a badass!”? Or when a spirit shows up during an evocation, I stop to remind it that I’m on an equal or greater footing than it?

Or maybe it’s practicing occultism but doing more drugs or sleeping with more people. Of course, when I say “doing more drugs,” I don’t mean meth or fentanyl; I mean “spiritual” drugs like pot or DMT. And when I say “sleeping with more people,” I mean doing it in a state where people still have access to reproductive health.

In other words, I mean ceremonial magick plus permissiveness with the safety net afforded by an affluent lifestyle and Democratic control at the state level—both of which are becoming rare in our failing democracy.

Or perhaps Thelemic magick is ceremonial magick, just with a particular aim such as Knowledge and Conversation of one’s Holy Guardian Angel. I think this is probably the best (mis)understanding of Thelemic magick, although it doesn’t help explain why Crowley also suggested so many non-magical practices to attain K&C, nor what the philosophy of true will is supposed to do to inform those practices.

Then you also have to make sense of Crowley’s strange definition of magick: the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will. His definition of magick encompasses all effective human action. This leads to a total secularization of Thelema where it becomes self-help or life advice—and not terribly effective advice at that, unless you start adding Ikigai, Why Discovery, or psychotherapeutic concepts to it.

And then after giving such a definition of magick, why does Crowley then go on to explain principles of ritual, magical formulae, purification, consecration, i.e., all the normal dimensions of ceremonial magick?

Because of these inconsistencies and seeming lack of coherence, it took me many years to even begin to understand what Thelemic magick was supposed to be and how it was supposed to relate to ceremonial magick or other spiritual practices.

The breakthrough for me occurred when I read this:

The method of Magick: Love the mode in which Will operates. The method of Magick in this—and in all—Work is: “love under will.” The word love (Ἀγάπη in Greek) has the value of 93, like that of Θελημα, will. This implies that love and will are in truth one and the same, two phases of one theme. Love is thus shown as the means by which will may be brought to success.

Djeridensis Comment on AL I.55-56

What I realized is that, while Thelemic magick may involve agency and the choices we make—spiritual or secular—it has a more original sense than that. It has to do with the dynamic coupling between Nuit and Hadit which gives rise to our sense that we are selves with a world in the first place.

In other words, magick is not first and foremost a form of human choice or spiritual practice. It’s a process occurring in reality which gives rise to our sense of choice and our sense of self—in the same way the operation of the Ruach is dependent upon the functioning of the Neshamah.

And because magick as a dynamic process grounds our more basic sense of self and agency, our normal attempts at self-empowerment and conceptualization cannot adequately capture it.

Of course it can be theorized. That’s what Thelema is by my understanding. What I mean is that we can’t get to the bottom of the processes forming us in real time, at least not directly. We have to approach them indirectly and symbolically by means of spiritual practices.

Or to put it more accurately, spiritual practices represent this underlying process’s attempt to work with itself, to optimize itself away from perennial spiritual problems. It’s not doing it primarily at the level of beliefs but rather in a symbolic, embodied mode.

Thelemic magick is the magick of magick. It is the power of human flourishing taking interest in itself.

It is Ἀγάπη.

The Two Foundations of Thelema

One of the most prevalant memes within Consensus Thelema is the idea that Crowley changed his mind so many times on so many different issues, it’s pointless to try to isolate any invariant “truth” within his thought. (Therefore it’s up to each individual to define for themselves what Thelema is blah blah blah let’s open another bottle of Apothic Red.)

But Crowley wasn’t that much of a creative genius. He had two insights, one theoretical, one practical.

The theoretical insight comes from the Kabbalah, mainly Samuel Mathers’s “Introduction” to Kabbalah Unveiled, his translation of Kabbalah Denudata. In particular, Crowley takes the idea of Ain, makes it the centerpiece or first principle of his world outlook, and draws implications from it that Mathers himself didn’t seem very interested in but which are reminiscent of how this idea was received in German language philosophy of the previous two centuries. By the time Crowley seriously engages with eastern philosophy, he has this Ain idea firmly fixed in his head, and he has a tendency to conform eastern philosophy (particularly Taoism) to it.

The practical insight—what I have called erotic liberation—probably comes from the fin de siècle decadent movement. It’s already on display in his 1898 poem, “Jezebel”. There you can see the mix of sadomasochism, cannibalism, and destruction (moral and physical) through eroticism that comes to define a lot of Crowley’s own spiritual praxis.

The practical insight probably precedes the theoretical insight, although the spiritual importance of the practical side lies in the fact that it reveals or discloses the first principle which organizes the theoretical side. In other words, Crowley may have insisted upon a mathematical deduction of his first principle in “Berashith” and Magick Without Tears, but neither mathematics nor reason in general are the main means by which one encounters the first principle in its fullness. That only comes about through the ecstastic practices Crowley eventually calls magick.

These ideas were formed whole in Crowley’s mind by the time he was 25 or so. Anything he encountered after that, he tended to wrap around or conform to these ideas.

As an aside, this is why it’s wrong to treat Thelema as a mere appurtenance to ceremonial magick, as though Thelemic magick is basically Golden Dawn ceremonial magic but done with a badboy attitude. While drawing shapes in the air and mispronouncing Hebrew are certainly aspects of the Thelemic magical tradition, that’s not the center of gravity of Thelemic praxis. One would be closer to the mark emphasizing transcendence through the encounter with potent (sexual) disgust—through the Pe in particular.

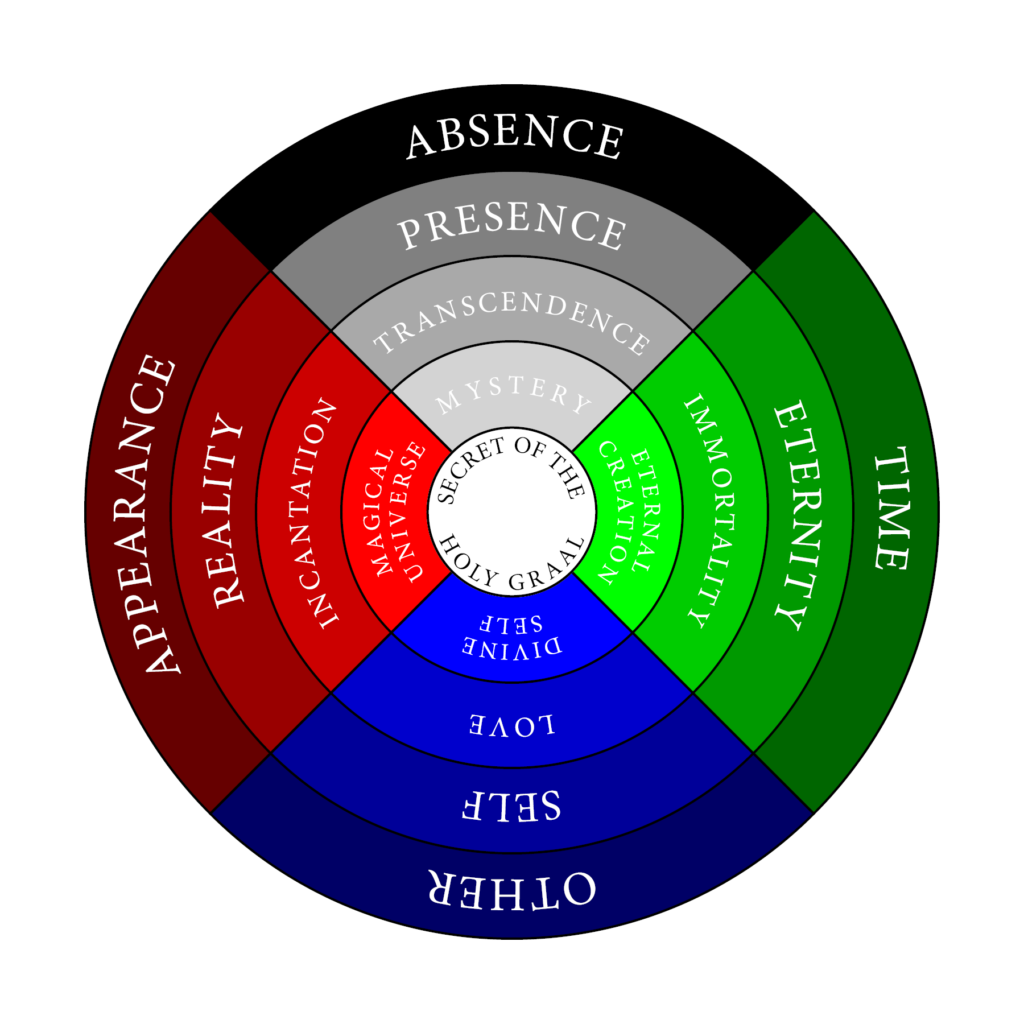

Why a circular Tree of Life?

Reflections on the Path in Eternity (Part 4)

I came to magick via an unsual path: through my interest in the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

Hegel was not a magician. He was a late-18th/early-19th century philosopher in the idealist tradition (a branch of thought taking influence from Descartes, Berkeley, and Hume, but which is usually seen as having its origin with the Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant).

But it was after I had been interested in Hegel for over a decade that I read Glenn Magee’s book, Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition. (You can read the introduction of the book here for free. It actually provides a pretty good orientation for how Hermetism differs from Gnostism and traditional Christianity.)

Magee persuaded me that Hegel’s philosophy of Absolute Idealism owed at least as much to Renaissance Hermetism (or Hermeticism as it’s sometimes called) as it did to rational thinkers such as Hume or Kant.

Magee understands Hermetism as a broad spiritual current which has a theological basis in the Corpus Hermeticum but which also includes currents such as Qabalah, alchemy, and magic.

Pretty much everything we consider to be the western magical tradition has its origins in Renaissance Hermetism, in particular the synthesis given to it by Cornelius Agrippa. (Really the only component missing from Agrippa’s synthesis is the tarot.)

For more on this I highly recommend Frances Yates’s Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. Certain aspects of her work are considered controversial now. I recommend reading Copenhaver, Hanegraaff, and Kingsley alongside her.

One of the main impacts Magee’s book had on me when I read it is that—oddly enough—it legitimized occultism for me.

Hegel was a philosopher I had spent over a decade studying both in and outside of academia. I considered a lot of my philosophical intuitions to be “Hegelian”. The experience was a little bit like having lived in a house for several years and then one day discovering a secret sub-basement that wasn’t on any of the building plans.

I was becoming familiar with the Qabalah right around the time I read Magee’s book (largely due to the work of my friend Daniel Ingram who also legitimized magick for me), so I recognized the Tree of Life in its usual top-to-bottom arrangement. But I was surprised to find out that there had been alternative arrangements of the sephiroth over time, including one in which they were presented as concentric circles.

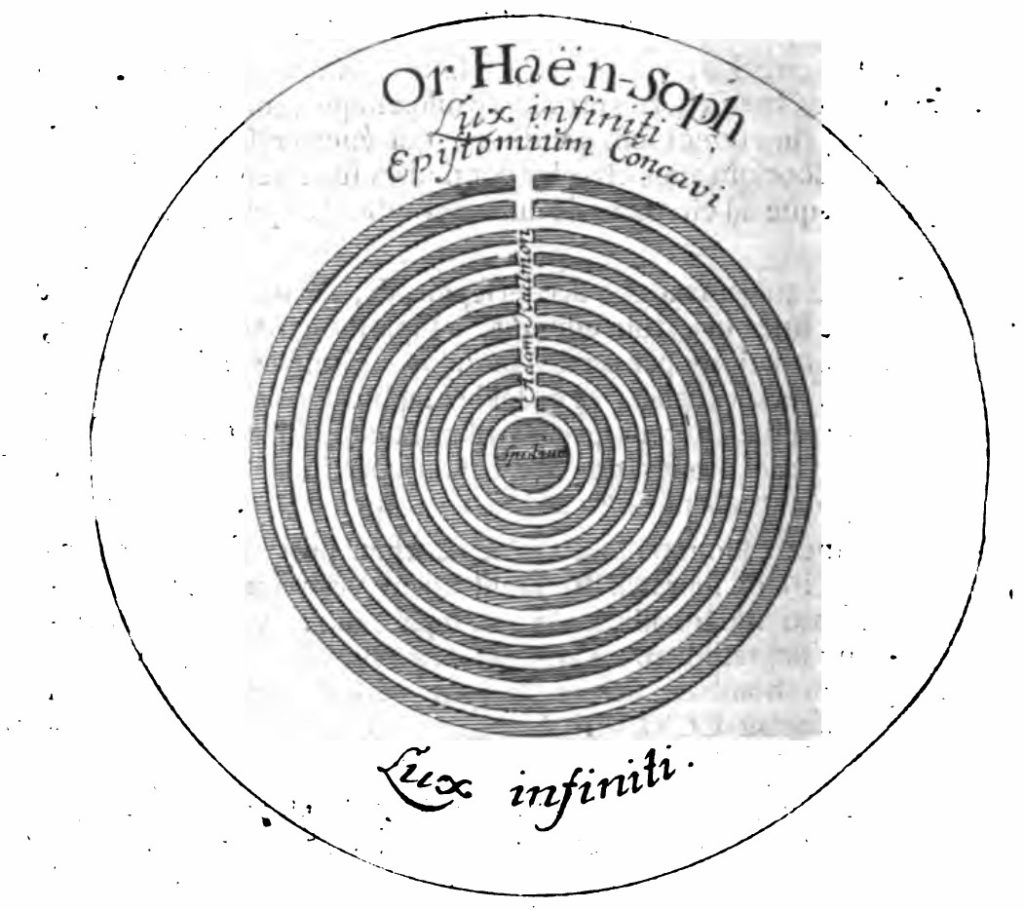

For instance, Johann Jakob Brucker gave them a circular arrangement in volume 2 of his influential Historia Critica Philosophiae (1742).

This diagram was Brucker’s attempt to illustrate a concept from the Lurianic tradition of Kabbalah, according to which each new act of creation or manifestation in the world is the result of a simultaneous contraction and expansion.

Isaac Luria and his followers envisioned the Ain Sof—the limitless infinity we previously identified with Nuit—as an infinite sphere in which a smaller sphere of empty space came into being through the tsimtsum, a primordial contraction or withdrawal of God.

It is into this empty space that God injects a ray of light which differentiates itself into the classical ten sephiroth. These were thought of as concentric circles of light filling the space within God created by the primordial contraction.

The first definite being that appears in the wake of the tsimtsum is Adam Kadmon (macroprosopus in the previous post). Adam Kadmon exists above the four worlds and mediates the light of Ain Sof into them.

Adam of the Bible—Adam Ha-Rishon—is an imperfect earthly embodiment of Adam Kadmon. While Adam Kadmon is spirit outside of space and time, Adam Ha-Rishon is spirit developing in nature, from the fall in the Garden of Eden and the loss of the immediate relationship to God, eventually to the recovery of that relationship in religion and mysticism (namely, Kabbalah).

(Ra-Hoor-Khuit is to Chaos as Adam Kadmon is to Adam Ha-Rishon.)

The implication of this concentric arrangement is that the material universe, individuals, and human history are not outside of the divine. Everything is in a certain sense “in” God. It’s just there in a corrupted or fallen state which has to be rectified over time.

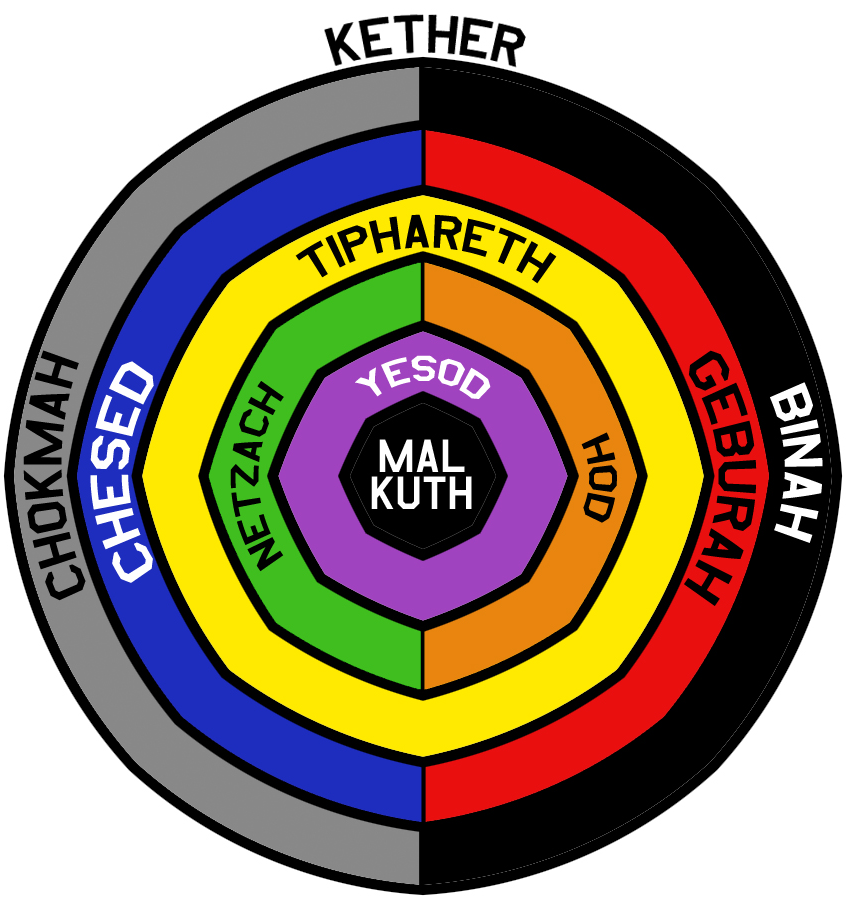

This sense of us being in God, of directly participating in the divine all the time whether we know it or not, can be occulted by the traditional top-down arrangement of the sephiroth, where it looks as though Kether, Ain Sof, and Ain are somehow way above us mere earthlings.

“A View from Kether” by IAO131

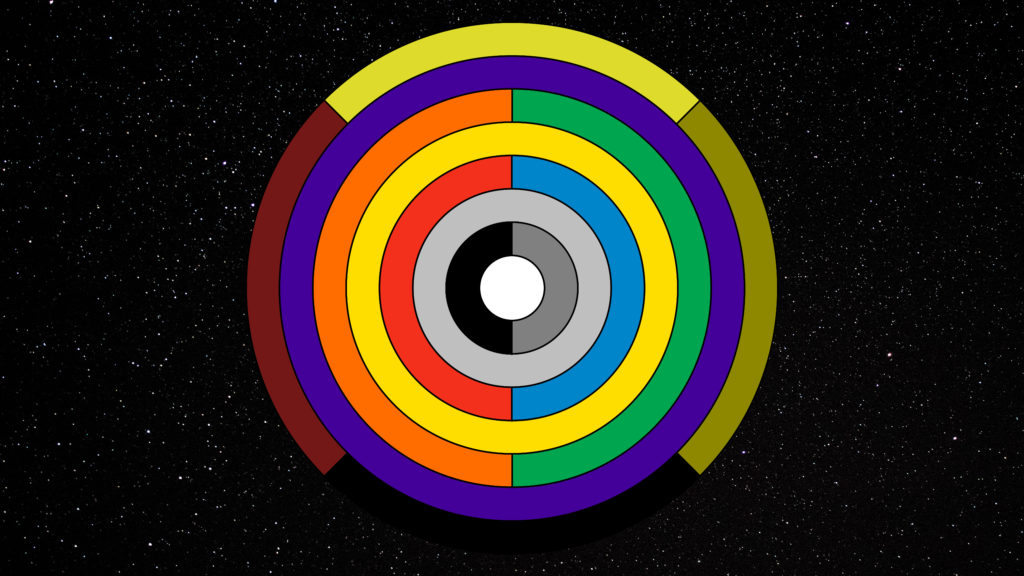

A few years later when I got into Thelema, I was pleased to see someone else had taken an interest in a similar arrangement. IAO131 created a diagram similar to Brucker’s in which Kether surrounds and contains the other sephiroth. My own version was inspired by his insofar as the sephiroth on the lateral pillars are depicted as semicircles rather than complete spheres.

What these concentric representations of the Tree of Life share in common is the implication that the reality we find ourselves in is one formed from an overarching, primordial, divine unity which divides itself.

There is some evidence in Crowley’s writings to support this view of our reality being the result of a self-division of God.

To know itself, each such Star, or Soul, must eat of the Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, by accepting labour and pain as its portion, and death as its doom. That is, it must reveal its nature to itself by formulating that nature as duality. It must express itself by a series of symbolic gestures ostensibly external to it, just as a painter reveals one facet of his Delight-Diamond by covering a canvas with colours in such a way that the picture seems at first sight to represent something outside himself. It must, in fact, repeat for itself the original Magick of Nuith and Hadith which created it.

New Comment on AL I.29 (emphasis mine)

AL I.29—of which this passage is a commentary—reads, “For I am divided for love’s sake, for the chance of union.”

We find in this passage echoes of the Lurianic idea of the fall as a temporary but necessary tragedy resulting from the diremption of an original, absolute whole (in this case the “Star, or Soul” of the individual).

The way to overcome this division is to repeat for ourselves the “original Magick of Nuith and Hadith” which created the star.

In this passage, Crowley presents the path toward liberation in artistic terms. The task is to see the world and the events in it, not as alien to our desires, but rather as vehicles for the manifestation of them. We are to view matter as (akin to) artistic medium.

The world loses its alien, painful character when it is understood and willed. When we can see the world as our own artistic creation, we have achieved liberation.

This is an interpretation of the Thelemic path of liberation I explored in my talk on the Magical Power of Art.

It was with something like this in mind that I formulated my own version of the concentric Tree of Life. However, unlike Brucker or IAO131, I reversed the order of the sephiroth. Rather than having Kether on the outside and Malkuth in the center, Malkuth is on the outside and Kether is in the center.

As it turns out, my reasons for doing this are numerous and complex. But before explaining any of them in detail, it’s worth mentioning that old adage that “the map is not the territory.”

I don’t believe sephiroth literally exist, let alone whether they are really, in any kind of metaphysical sense, related to one another externally or internally, or whether Malkuth can really be said to be at the center or not. That’s not really the point of a diagram.

In this context, the purpose of the diagram is to serve as a heuristic. It’s an attempt to convey some complex ideas in a simplified format that makes them easier to comprehend.

There could well be certain aspects of Thelema that are better captured by having Kether on the outside and Malkuth in the center, just as there are aspects that are better captured by the usual hierarchical (top-down) arrangement.

All of that being said, there are a lot of spiritual, metaphysical, theological, and soteriological assumptions packed into this simple decision to put Kether at the center and Malkuth on the outside.

Some of them require a lot of explanation and carry with them a lot of implications, so rather than go into any of them in depth right now, I’ll just list them succinctly.

- Repeat = Defeat. Let’s present something familiar in an unfamiliar format to discover new things about it.

- The journey is inward, out outward. Crowley described the work of A∴A∴ (in contrast with the work of O.T.O.) as a process of going inward toward the three supernal sephiroth. Without taking it too literally, that implies a certain spatial relationship. And since all the sephiroth are to be found “in” Malkuth, this links Thelema with what might be termed a chthonic counter-current in Western mysticism.

- The Khabs is in the Khu, not the Khu in the Khabs. Again, this implies a particular spatial relationship. This also implies that divine reality is not some original whole we were cut off from and have to get back to. This core spiritual idea sharply differentiates Thelema from Hegelian Idealism, Gnosticism, or even from Kabbalah. In Thelema the individual really is primary and irreducible in a way that you just don’t find in those other traditions.

- Thelema is about 2, not about 1. It’s all about the relationship between Hadit and Nuit. In order for there to be a love relationship between Hadit and Nuit, Nuit must be other than Hadit. That doesn’t work if Hadit and Nuit are merely parts of a primordial, original whole.

- It’s all about the going. Experience matters. Change is real. It is powerful, it is divine, and it is meaningful. The O.T.O. teaching on the Path in Eternity is as central to Thelema as are the teachings of A∴A∴ on the Holy Guardian Angel and the Abyss.

- It’s magick, not just mysticism. Going implies change, change implies magick, magick implies the Will. Willing implies traditionally masculine qualities such as mastery, overcoming, and expansiveness in addition to the feminine characteristics of dissolution and surrender that are particular to mysticism. Both sides are necessary for a complete understanding of Thelema.

I don’t know yet if I’m going to write posts about all of these. If there are particular ones you definitely want to hear about, though, let me know in a comment.

Being a conduit for the divine

One of the salient differences between Thelema and the Buddhism of the Pali suttas is that in Buddhism incarnation is seen as something to be overcome and abandoned, in Thelema it serves the purpose of the self-realization of a higher, divine consciousness.

Thelema has that Buddhistic idea of seeing through the illusion of a separate self. When everything you consider to be “you”—what in Buddhism are called the aggregates or heaps—is seen to rightfully belong to Nuit, then the way is clear for the true self (Hadit) to unite with Nuit. This is what I’ve called the path of erotic liberation or surrender to the divine feminine.

But that’s only one half of the story. If we leave it there, we get a Buddhistic version of Thelema, but then you’re left wondering why Hadit would have created the sense of separation from Nuit in the first place. It’s what I referred to as hiding your car keys on yourself in my talk Light of the Shadow.

The idea in Thelema is that what you conventionally call “you” is not simply an obstacle to be overcome but instead serves a divine purpose. In the Noble Eightfold Path, you see permanently through the illusion of self, you permanently relinquish attachment, and it’s like pulling the eject lever on the cockpit. You’re off the ride. That’s not the Thelemic story.

In Thelema “you” (conventionally so-called) serve an intermediary function between the divine and itself. Once the true nature of sensation is understood, you become a daimon or a magician or a navi (a forth-speaker on behalf of the divine). But you can only serve that function once the delusion of separation from the divine has been destroyed.

As I said in “Light of the Shadow,” we sometimes operate under the delusion that the senses separate our consciousness from reality or cut us off from the truth. This is actually a common sense notion. But if the senses are themselves divine, then the problem is not that we have senses; the problem is that we don’t know how to use our senses properly—with the result that they end up using us instead. And so the path of liberation requires a kind of “aesthetic education” (after the Greek word for sense perception, aisthēsis).

Separation and illusion

One of the things that took me awhile to grasp is that the main object of spirituality—the base matter you’re working to transubstantiate—is your own sense of spiritual longing.

If you think about it, what was there before you encountered spiritual traditions and spiritual practices? There was the sense of something missing, something absent. There was a vague sense of dissatisfaction, not with one thing or another, but rather with conditioned existence itself. This is what drove us to seek spiritual traditions and practices. This is what made them appealing in the first place: that they seemed like solutions to this sense of disconnect from something higher.

Spiritual traditions and practices do not fulfill that desire for transcendence. For that matter, neither do peak spiritual experiences, no matter how profound, at least not for long. For every peak spiritual experience, the dryness returns like thunder following lightning. For each new spiritual plateau you hit, the sense of absence returns in a new, vaster form.

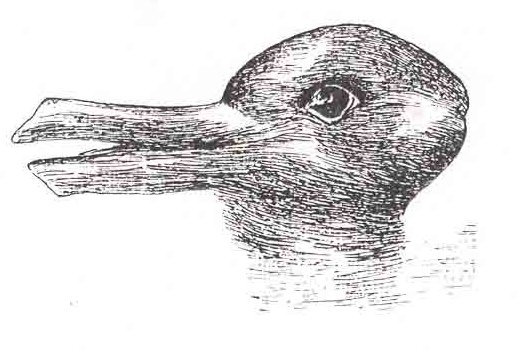

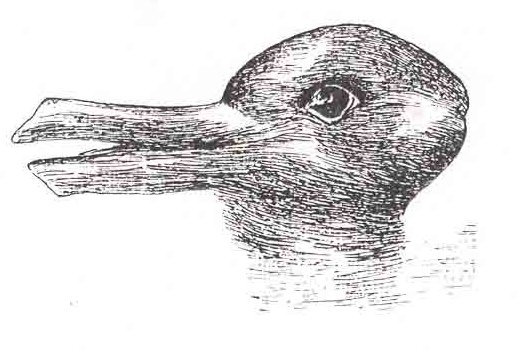

What happens for some people is that, after pursuing these spiritual experiences for a long time, they eventually turn around and bring their attention to the desire or sense of separateness itself. They manage to look at it a certain way. I don’t know exactly how to explain how to do this or even describe it. I just know it happens. And then there’s kind of a duck-rabbit flip that happens. The sense of separation itself is seen as presence.

That’s the moment of realization.

Imagine you’re aspiring fervently to union with your Holy Guardian Angel. You’ve experienced samadhi with your HGA on occasion, but there’s still something “missing”. There’s still the sense of a gulf between you and the divine. But then at some point, this “flip” occurs.

The “flip” is not suddenly thinking that your HGA is inside of you. That’s an extremely tempting interpretation, since we’re constantly told that God is inside of you. That’s not it. There’s something far more profound than that.

It’s more like the distance between you and God is God.

You realize that what you thought was God or your Angel is just a thought-form. It’s conditioned. It comes and it goes. But there’s something that doesn’t.

And then you look around the room or out your window and realize that God is everywhere and in everything. Basically wherever the sense of separateness is—me here, the object there—that’s oneness, unity, God. That’s the Vision of Pan.

But this is why if you don’t trigger a profound Dark Night of the Soul, it’s very difficult, maybe impossible, to achieve spiritual realization. Spiritual realization is the transformation of the sense of separateness—the darkness—into presence or gold.

But—and this is the part that’s difficult to grasp—it’s not overcome by replacing it with a presence. The Holy Guardian Angel isn’t going to show up and fill an HGA-shaped hole in your heart. If that happened, that would be just another experience. It would come, hang out for a bit, and then it would go. As profound as that experience might be, it would not be different in kind from eating a sandwich.

It’s more like the HGA-shaped hole in your heart will in and of itself be seen to be the presence of the divine. But that HGA-shaped hole is not special. It’s just a catalyst. Because every absence you look at after that will be seen as a type of presence.

This is another reason non-duality is a non-starter. Non-duality is the philosophical idea that separation (“duality”) is “just an illusion” and can be safely ignored.

Bullshit!

Yes, everything is an illusion. This world we think we exist in is about as thick and sturdy as a wet piece of toilet paper. You could put your little finger right through it if only your little finger weren’t also made of wet toilet paper.

And that’s the problem right there. “Non-duality” is just another thought-form. It’s just another concept. As such, it is made of the same flimsy material as everything else. The problem is that it surreptitiously sets itself up as something different, as being a concept which—unlike all those other concepts that posit dualisms—is somehow superior, somehow has a unique grasp on truth. As such, it establishes an even more insidious duality!

The proper response to the illusion of duality is not to reject the illusion of duality. It’s to respect the illusion of duality. To slowly draw close to it—closer than the overwhelming majority of human beings ever have—and to see it for what it truly is in and of itself.

The method of respecting the illusion in order to understand its true nature is magic.