Until we have properly cultivated love, the extremes of Thelemic magical and mystical experience remain off-limits.

Love under Will

Love under will means learning to care about what is worthy of our attention.

Self-Love and Love of God

It’s an intellectualization of an experience which really can be transformative of the self, but having certain concepts or preconceptions or expectations can actually make the experience less likely to occur. You’ll miss out on the real thing because you were searching for a counterfeit.

Yoga and eroticism in the Platonic tradition

The Good and the One in Proclus

The highest principle in Platonism is the Good. The identity between the Good and the One is established by Proclus in the 13th proposition of his Elements of Theology.

All that is good is the unifying principle of its participants, and all union is good, and the Good is the same with the One.

For if the Good is the preserving principle of all beings (for which reason it is also the object of desire for all), but that which is preservative and connective of the essential being of every being is the One (for all are preserved by the One and dispersion removes every being from its essential being).

For the Good completes and contains those, in which it is present, according to one union.

And if the One is collective and connective of beings, then it will perfect every being by its own presence.

Accordingly then, it is also Good for all these to be united.

Proclus, Elements of Theology, Proposition 13

The argument is extraordinarily terse, so it merits unpacking. But the unpacking will not only tell us why the Good is also the One but also what the characteristic function of the One is such that it is good.

Starting with the second paragraph, Proclus argues from the Good to the One by means of the way in which the Good preserves and connects the “essential being of every being” that participates in it.

So to the extent to which something participates in the Good, it is moving—through time—toward a state in which it is more exactly what it in essence is. In other words it is moving toward perfection. And the extent to which it is moving away from the Good, then over time it is decaying or falling away from what it is.

The principle way in which the Good allows beings to be what they essentially are is through its “preservative and connective” function. In other words, it accomplishes this by making and keeping them whole over time.

To put it another way, all material things are composite and subject to change. If the component parts of something fly off in all directions, the thing is destroyed. But to the extent to which the parts maintain their proper connections with one another, the being of which they are parts maintains its unity, its wholeness. But wholeness or unity as such is the One, and therefore the Good is also the One.

And then he runs the argument the other way in the fourth paragraph. The function of the One is “collective and connective”. To participate in the One is to experience greater unification with oneself, a greater degree of wholeness, and so one moves toward perfection or being what one in fact truly is. But we already know that this is what participation in the Good rewards one with, and so the One is also the Good.

Proclus’s argument relies upon the preservative and the connective functions of the Good and the One.

He assumes that the Good is the preserving principle (sostikon—from sozo meaning salvation) of all beings, and that the One is the preservative (sostikon) and connective (sunektikon) principle of the essential being (ousia) of every being. By virtue of the preserving and connecting, all are preserved (sozetai—again, “saved”) by the One.

This is important not only because it is the fulcrum around which Proclus’s argument turns, but it also gives us insight into the essential nature of the One and how it functions. We might say the highest ontological principle in Platonism is a principle whose main function is to bring about preservation or “salvation” (sostikon) by keeping together (suntereo) or by synthesis (suntithenai).

Logos and Synthesis

Probably the most famous modern proponent of a “synthetic” ontology is the philosopher Immanuel Kant. Kant famously declared all principles of metaphysics (of which ontology is a part) to be synthetic a priori. This means that such propositions must be justified independently of empirical experience, but that they also cannot be justified solely by the meaning of the terms involved. An example of such a synthetic a priori statement for Kant would be, “Every event has an antecedent cause.” There is no way to prove such a statement on the basis of examining particular occurrences, but it is also not possible to derive the term “antecedent cause” from analysis of the dictionary definition of “event” which just means “change from one thing to another.”

The way in which Kant proposes to justify synthetic a priori propositions—and hence provide a secure foundation for metaphysics—is by grounding them in subjective processes of the mind which are nevertheless necessary for having any empirical experience at all. Kant argues that there are certain rules of experience which are not derived from experience but which the mind structures experience in accordance with. In other words, the underlying logical architecture of the mind necessitates that sensations be connected with one another in certain ways, and one of these ways in which the mind connects things is according to the rule of cause and effect.

To put it another way, logic projects semantics on to the world. And the way Kant argues the mind projects its meaning on to the world is through a process he terms synthesis.

(At this point, with the subjectivizing of synthesis and the world-building function, we are closer to the Thelemic understanding of these categories than the Platonic understanding.)

Our English word logic derives from the Greek word lógos, which means “speech, oration, discourse, quote, story, study, ratio, word, calculation, or reason.” The Greek word for “I speak” is légō. Both terms are derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *leg- which means “to collect, gather.”

So in the Greek word for speech we have the idea of collecting or of synthesis—the same function Kant assigned to the underlying architecture of the human mind and the same function which is so crucial for understanding the One in the Platonic tradition.

So we might go a step further in our explication of the One and say that, while its essential functions are connecting, keeping together, and preserving/saving, this essential function is carried out, or is in fact identical with, a kind of speech.

To put it somewhat differently, the One projects a “logic” on to beings—let’s call it an invariant cosmological structure or set of laws—but rather than this logic subsuming beings or somehow fixing them into place, it has the seemingly paradoxical effect of “saving” them (from decay) in such a way that they are allowed to go on to be precisely what they are in their essence (ousia).

To say it yet another way, this time in more explicitly theological language, divine logos—a power which the Hermetic tradition assigned to Thoth-Hermes and called the Second God or the Son of God—frees things to be what they are in themselves.

Eros and Divine Logos

In the Orphic Hymn to Aphrodite, we find the Greek goddess of beauty and love described as “she who causes beings to mate” (zeukteira—from zeuktēr, “one who yokes”). A couple of lines later, she is described in the same way, this time with regard to the cosmos itself: “and you have caused the cosmos (kosmon) to couple (upezeuxo)”—literally, you have “yoked” the cosmos.

The Greek word for yoke is zugós, which comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *yugóm, which means to join. This is the same root from which derives the Sanskrit word yoga, which also means yoke or union and which eventually acquired the connotation of union with the divine.

So in the poem we see Aphrodite described according to two functions. She “yokes” mortal lovers together—i.e., she causes them to fall in love and to mate—and she also causes the cosmos itself to couple or to join. And it’s clear from the play on words in the Greek that the author intended for the mind to associate the one function with the other.

But we have already seen that joining and connecting—especially when looked at from the cosmological or metaphysical perspective—is the function of the One. Not only that. It is the essential function of the One and also that which makes it the Good. To speak of Aphrodite as serving as cosmological matchmaker, therefore, is to endow her with the power of the One, the highest ontological principle. In fact it is to say that she is identical with the One.

Looked at from the other side, we might say that in addition to its ontological and “logical” functions, the One also has an erotic function. In other words, our account of the way in which the One “connects and preserves” through “speech” is incomplete unless we also understand this connecting and joining from an erotic and conjugal perspective.

To be clear, I am not saying that the One is in fact Aphrodite. I’m claiming two things. (1) There is an erotic dimension to the characteristic activity of the One. As a mnemonic, one might represent that function by the Greek goddess Aphrodite in the same way one might represent the logical function of the One by the Greek god Hermes. And (2) we should be careful forcing a separation between erotic love and spiritual love. Eroticism is not mere carnality but has a hieratic potential. We will explore this potential in depth in the next section.

Finally, when we speak of something being something, we can say this in many different ways. For example, we can say that it is, i.e., that it exists, but we can also assign a predicate to it, e.g., “The horse is fast.” The predicate is fast is not identical with that which is identified by The horse—it is different—but it is joined with it through the function of the verb to be. But by joining this general concept fast with the particular horse, we are in fact revealing something essential about the horse itself, viz., that it is fast. So again, somewhat paradoxically, by going away from the horse itself to something other than the horse, we do not turn away from or cover over the horse but instead reveal something true about the horse itself.

This function of the verb to be, when it joins a predicate with a subject, is called the copula. It comes from the same root from which we get the English word copulate. Something of the erotic dimension of logic and ontology is captured in our using that particular word to describe predication.

Love and Liberation

One of the things we were at pains to emphasize earlier is that participation in the One does not efface beings. To realize that “all is one” is not to see all things as the same thing. In fact the One is not a thing at all, and so participating in the form of the One does not reduce all things to the same thing. Rather, it frees beings—saves them in the language of Proclus—to be what they essentially are in themselves as self-unified beings. Insofar as it makes sense to speak of the One projecting a kind of logical structure on to beings, the purpose of this structure is not to ensnare or enclose them but paradoxically to release them into their ownmost being. They are released to the world, but more importantly, they are released to themselves and in a sense to their own care. We can now refine this conception in light of the teaching of “Orpheus” by saying that this joining-freeing is also divine loving.

From the perspective of ontology and cosmology we might say that the Platonic doctrine of the One as developed by Proclus is in some ways quite similar to “eastern” cosmologies, particularly yogic or “tantric” conceptions according to which the phenomenal universe is the result of the sexual union of Shiva and Shakti, or lingam and yoni.

From a soteriological point of view we might say that there must be a tight association between (a) knowing oneself, (b) that direct knowing of God which the Greeks called gnosis, and (c) eroticism. The One joins disparate things together to become whole beings in what we might term cosmological marriage or coitus. But in the case of a human being, knowledge forms part of that whole. So to achieve perfection or union entails the power of the individual not only to turn back on their self but to also know that they are turning back and to know precisely what it is they are turning back on. In the case of a conscious being, the reflection is explicit, willed, and clear. So the perfection of the individual entails what Hegel may have termed the satisfaction of self-consciousness. But as we saw at the beginning, to move toward perfection and to participate in the Good are identical. Hence, knowing oneself and knowing God are identical.

The erotic dimension of salvation enters when we recognize the yogic dimension of self-unification. To gather oneself together into a singular awareness is what is termed in the Pali Buddhist tradition ekaggatā or one-pointedness. It is one of the factors of samādhi or meditative absorption. Other factors include píti (rapture or joy) and sukha (happiness). The joy and happiness attendant upon samādhi are subtler than “gross pleasures” but they are more enduring and more reliable, and hence in the context of Theravada Buddhism, samādhi is considered to be an important intermediary set of experiences between ordinary consciousness and complete awakening.

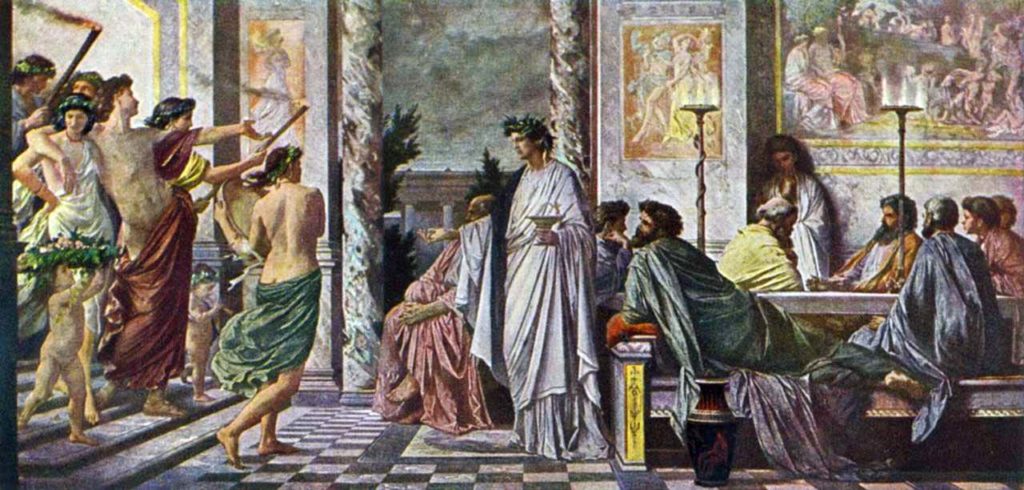

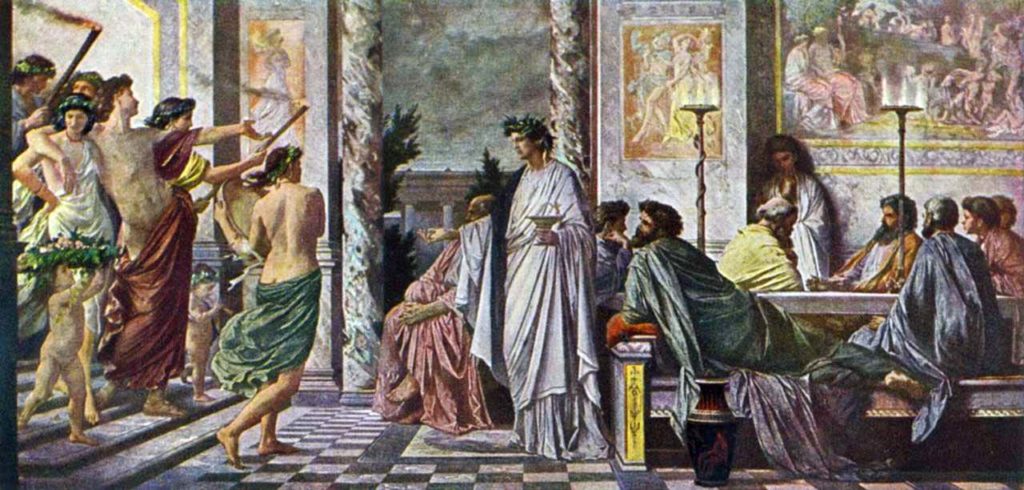

There is a similar intermediate experience described in the Platonic tradition between ordinary consciousness and direct knowledge of the One, which Plato in the Symposium describes as the idea or the form of beauty. In the experience of the form of beauty, it is linked with justice and goodness, and—most importantly—it is apprehended as the principle of unity itself.

I don’t think that Plato means to reduce the One to the experience of beauty. More likely he intends the idea of the beautiful to be an apophantic quality of the One: something like the closest correlate to the One that one may encounter by means of sensation. (The Greek word for sensation is aisthēsis from which we get our word aesthetics.) It is possible that by the apprehension of the idea of the beautiful Plato has in mind an experience not very different from that of samādhi in the Buddhist and Hindu traditions.

If that is the case, then the Platonic spiritual path might be said to consist in the pursuit of deeper and more profound experiences of beauty until apotheosis occurs. The path described in Symposium is one in which the soul progresses from coarse beauty to ever more refined forms of beauty, until one moves from loving beautiful things to craving Beauty itself. The Platonic spiritual path is therefore equally an erotic and aesthetic path of liberation.

Implied in the Platonic spiritual path is a challenge to the idea that we can cleanly separate erotic love and spiritual love. As Plato illustrates in Symposium, the first pursued deeply enough leads to the second.

It is now clear that adequately understanding erotic love can lead us to a direct experience of Beauty and then the One. But is there anything that our experience of Beauty and the One can teach us about erotic love? In other words, how should spirituality inform our romantic and sexual relationships?

Between the Romantic and the Divine

It seems to me one might construct a “Platonic” approach to sexual and romantic relationships along the following lines.

Normally when we use the phrase “Platonic love,” we mean mere friendship. While much of what I will say applies to friendship, I don’t mean friendship exclusively. I also and primarily mean romantic and sexual love relationships. With that in mind, I would suggest the following principles:

- We don’t necessarily fall in love with people who are good for us. We just tend to fall in love with people who are familiar. If your upbringing was wonderful, you’re one of the lucky few who are perhaps attracted to people who are also good for you. For the rest of us, read on!

- Look for someone you admire. Find someone with admirable qualities, someone you can look up to. Find someone who at least some of the time models what you consider to be good in the world. This applies to all relationships, not just romances.

- Find someone who wants what is best for you and in you. You want a person who is happy for you when you’ve achieved something meaningful and who will be there for you when you’re going through a rough time. Avoid people who are envious of you or who are resentful of your happiness as much as possible.

- Understand that the relationship itself is prior to the individuals composing it. What I mean is that you are not in charge in the relationship, and your partner is not in charge in the relationship. The relationship itself is in charge. When you have a difference with your partner, the “winner” is the person who wants to do what is best for the relationship. This is because:

- A relationship is more than the sum of its parts. It has to be, otherwise we wouldn’t bother with them. If we could get what we needed by ourselves, for ourselves, we wouldn’t bother with relationships. The whole point of a relationship is that it can provide for you in a way you cannot immediately provide for yourself. You ruin this power of a relationship when you just try to get things for yourself. Make the relationship healthy, and you can get so much more than either of you could get just trying to be selfish.

- At its deepest level, a relationship is a spiritual entity. It is a logos. It has a certain intelligibility and wholeness all its own. It is a living being. Like the One itself, the purpose of the relationship is to unite its component parts (the individuals in the relationship) through love and to bring them to fulfillment and wholeness in themselves. So do not consciously devote yourself to your partner. Consciously devote yourself to the partnership, and by its divine power it will unite the two of you.

- Investing in the third entity, the partnership, can mean a lot of things, but much of it comes down to fairness and reciprocity. You give freely of yourself to your partner because you know they will do the same thing for you. This frees you of self-obsession and brings freedom and well-being. This isn’t just based on Platonic theory; it also seems to be based on biology. Stan Tatkin has written a few books about this which you may want to check out. The “spiritualizing” of it is mostly mine, though.

What is Thelema?

Thelema is a religion founded in 1904 by the English poet and mystic, Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), who is regarded as its prophet. Those who follow the path of Thelema are called Thelemites.1

Thelema (Θελημα) is a Greek word for will, and the essential teaching of Thelema is “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” Of this teaching Crowley said,

“Do what thou wilt…” is to bid Stars to shine, Vines to bear grapes, Water to seek its level; man is the only being in Nature that has striven to set himself at odds with himself.2

From this we may infer that the essential teaching of Thelema is that each person ought to live in accordance with nature as expressed through their individual being. In this respect, Thelema is similar to Stoicism, Buddhism, or other religions which teach us to live according to the laws set by nature rather than God or human beings. Yet the Thelemic view of the universe according to Crowley differs in fundamental respects from what is taught in other religions and philosophies.

“Had! The manifestation of Nuit. The unveiling of the company of heaven.” (AL I.1-2)3

The foundation of Thelema is Liber AL vel Legis, which is Latin for Book AL or the Book of the Law.4

The Book of the Law was dictated to Aleister Crowley in Cairo, Egypt in 1904 by a spiritual being that called itself Aiwass. This book declared a new age for humanity, the Aeon of the Child, and proclaimed a new law for the conduct of all human beings: Do what thou wilt.

The universe described by the Book of the Law consists in two irreducible entities or concepts: the totality of possibilities of all kind, and any point of view on those possibilities. The first is symbolized by the Egyptian sky goddess, Nuit, and the second is represented by the Egyptian sun god, Hadit.5

“Every man and every woman is a star.” (AL I.3)

Experience arises when Hadit (the self of each individual) unites with some possibility inherent in Nuit (the spatiotemporal universe). Each person is “an aggregate of such experiences, constantly changing with each fresh event” or a star.6

Crowley describes each individual star or consciousness as an absolute monad: simple, utterly indestructible, as well as omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent. These are characteristics usually attributed to God, and indeed, Crowley taught that each star was the center and origin of its own universe.7

“For I am divided for love’s sake, for the chance of union.” (AL I.29)

Throughout our lives, and even throughout the course of a day, many events occur that imply oppositions or dualities. We experience pleasant versus unpleasant sensations, sorrowful versus happy occurrences, success versus failure in our endeavors, cruelty versus kindness in our actions, self versus world, self versus others, and many more. But the universe appears to us this way, because it is only by means of opposition that our Hadit or god-self can have experience and learn about itself. While each of us encounters constant opposition from the world and others, this opposition is both necessary and willed.8 From this, the supreme teaching of Thelema follows:9

“Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” (AL I.40)

Crowley speaks of the will in two basic senses. On the one hand, each person has to discover for themselves what their purpose in life is. This could involve discovering which particular career or form of service suits your personality best and dedicating yourself wholeheartedly to it.10 It also means being free to express one’s individuality artistically and sexually, to work and to play as suits one’s own nature, and even to move across the face of the earth without interference from others.11 Crowley calls this the finite will or your will in the context of this life.12

Then there is your will in eternity or your infinite will, which is the will of Hadit—your true self—to explore every possibility available to itself, even across many incarnations. Crowley calls this the Great Work or the union of Hadit with Nuit.13

These need not be seen as two separate wills but rather two perspectives on the same will: the will seen from the perspective of this incarnation, where each moment presents us with the choice between doing our will versus not doing it, and the perspective of eternity, wherein every occurrence accords with our will, because every moment is necessary and perfect in and of itself.14

“Love is the law, love under will.” (AL I.57)

Every event whatsoever is an act of love, as each consists in the uniting of Hadit or the divine self of each individual with a possibility inherent in Nuit.15 While it is technically impossible not to do your will (seen from the infinite perspective), it is possible (from the finite perspective) to desire not to do your will, and from this arises suffering.16 It is therefore up to each of us to discover for ourselves what our true will is and to accept and desire to fulfill it rather than thwart it. Crowley calls the methods for achieving this magick.17

“Remember all ye that existence is pure joy; that all the sorrows are but as shadows; they pass & are done; but there is that which remains.” (AL II.9)

Since all events are acts of love under will, it follows that, at its very foundation, existence is joyful. Sorrow arises when we think of any two things as opposed to one another. Some one event pleases us so we call it “good,” and another is unpleasant so we call it “bad”. But they are all fundamentally “good,” because they are all the effect of Hadit loving Nuit, which itself is the natural result of each of us doing our will.18 This love of Hadit for Nuit eventually culminates in the union between the two which occurs at death, and therefore “death is the crown of all.”19

While there is more to Thelema than what is presented here, the rest are largely implications or practices intended to achieve these ideals. For further information, the reader is encouraged to explore the resources footnoted in this section.

1 https://oto-usa.org/thelema/

2 “Notes for an Astral Atlas,” in Magick in Theory and Practice (MITAP), Appendix III.

3 Chapters and verses of the Book of the Law are notated AL Chapter.Verse

4 AL is a Hebrew name for God.

5 Introduction to The Book of the Law (Intro).

6 Intro.

7 Intro and New Comment (NC) on AL I.3.

8 NC to AL I.29.

9 NC on AL I.3

10 MITAP (Introduction) and Liber CL (Section I).

11 Liber LXXVII.

12 Liber CL (Section I).

13 Ibid.

14 Intro.

15 Ibid.

16 NC on AL 1.51 and Liber CL.

17 Intro.

18 Djeridensis Comment on AL II.9.

19 NC on AL II.72.

References

- Crowley, Aleister. The Djeridensis Comment

- Crowley, Aleister. Liber CL

- Crowley, Aleister. Magick in Theory and Practice

- Crowley, Aleister. The New and Old Commentaries to Liber AL vel Legis, The Book of the Law

- Liber AL vel Legis sub figura CCXX with Introduction by Aleister Crowley

- United States Grand Lodge Ordo Templi Orientis

The argument against compassion

Please Note: It is up to each individual to decide this question (and all questions regarding Liber AL vel Legis) for themselves by appeal to Crowley’s writings (or however they see fit).

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about Crowley’s condemnation of compassion. This condemnation is in the Book of the Law itself (AL II.18-21), and Crowley himself elaborates on it in many places. Here are just two examples:

Compassion, the noblest virtue of the Buddhist, is damned outright by Aiwass. To “suffer with” some other being is clearly to cease to be oneself, to wander from one’s Way. It always implies error, no Point-of-View being the same as any other: and in Kings—leaders and rulers of men—such error is a vice. For it leads straight to the most foolish Rule ever laid down, “Do unto others as you would that they should do unto you.” (Djenerensis Comment to AL II.21)

And:

Of what use is it to perpetuate the misery of Tuberculosis, and such diseases, as we now do? Nature’s way is to weed out the weak … We must therefore go back to Spartan ideas of education; and the worst enemies of humanity are those who wish, under the pretext of compassion, to continue its ills through the generations … Let weak and wry productions go back into the melting-pot, as is done with flawed steel castings. Death will purge, reincarnation make whole, these errors and abortions. Nature herself may be trusted to do this, if only we will leave her alone. (New Comment on AL II.21)

But the condemnation of compassion does not necessarily entail indifference toward the distress of others:

Pity, sympathy and like emotions are fundamentally insults to the Godhead of the person exciting them, and therefore also to your own. The distress of another may be relieved; but always with the positive and noble idea of making manifest the perfection of the Universe. Pity is the source of every mean, ignoble, cowardly vice; and the essential blasphemy against Truth. (“Duty”)

In other words, acts of kindness are permissible if they are carried out for reasons other than pity. It’s not the effect that is condemned but the passion that could motivate it.

Of course one can cavil endlessly over what words mean, but these statements do not strike me as any more ambiguous than statements Crowley makes on subjects such as individual liberty and sexual freedom that many Thelemites take for granted.

The condemnation of compassion is not a standalone claim, something merely tacked on as an afterthought to Thelema. Crowley presented an argument against compassion that proceeds from premises accepted by many Thelemites, viz., love under will and the joyous nature of existence:

(1) “All Events are Acts of Love Under Will.” (DC on AL II.9)

(2) “[Therefore] Hadit now sayeth to all that they should be mindful of the Nature of that which exists; it is pure joy” (Ibid)

(3) “The highest are those who have mastered and transcended accidental environment. They rejoice, because they do their Will; and if any man sorrow, it is clear evidence of something wrong with him.” (NC on AL II.19)

(4) “[Those who suffer] had better “die in their misery”; that is, cease once and for all to react so feebly and wrongly as they do: for such a Point-of-View as they shew forth is not to be endured. It is not truly Hadit at all; not any one Point, but a shifting fulcrum: let it be no more counted among True Things.” (DC on AL II.21)

The argument is a little obscure between (2) and (3). A generous reconstruction might be:

- Any change from one thing into another is willed on the part of Hadit. But this is the same thing as Hadit once again loving Nuit, thereby dissolving the previous moment into ecstacy.

- So despite appearances, each moment is joyful or blissful. Dukkha is not the preeminent reality; ananda is.

- If one fails to perceive this, the fault lies with the individual who is misperceiving things, not with reality itself.

- Therefore, don’t feel sorry for the person who is miserable. They’re doing it to themselves.

Leaving aside whether the argument is sound, it is simple and clear enough to understand. That being the case, these seem to be the possible responses to it:

(1) There’s something wrong in AC’s argument here, either the premise or the inferences connecting the premise to the conclusion.

- Since the premise is love under will—in other words, a part of Thelema many Thelemites agree is its essence—then if the problem is with the premise, Thelema (at least as many Thelemites seem to understand it) is nonsense. One should probably not be a Thelemite.

- If it’s the inferences, then the condemnation of compassion in Liber AL is not what AC thought it was. This challenges the notion, oft repeated by AC himself, that he was in a unique, privileged position to interpret the BotL. (Crowley also denied he was able to exhaust the meaning of the book by means of his own analysis.) It also challenges at least the literal interpretation of The Comment, a Class A text, which O.T.O. policy and the behavior of a lot of Thelemites is based on.

- The premise (also) does not mean what AC thought it meant. This leads to the consequences of 1(b) and the additional consequence that there is no reason to agree on what the essence of Thelema even is. Some would undoubtedly celebrate this result.

(2) Both the premises and the inferences are correct. The problem is with those of us who still “suffer with others”. We’re not living in accordance with nature. We can either:

- Get our act together and “be Hadit” and “be kings,” or

- Choose not to. We’re always free to do that. Aiwass’ word for such people is “slaves”.

(3) Both the premises and the conclusion are correct, but one will just not be consistent on this point. Most followers of most religions aren’t consistent, and cognitive dissonance isn’t exactly rare, so this wouldn’t be anything new. Depending on how they interpret AL II.32, one might choose to fall back on Aiwass’ condemnation of reason.

While I present (2b) and (3) as separate, I think they’re effectively the same. In other words, I think being inconsistent on this particular point is just what AC (and for that matter Aiwass) meant by being a slave.

Another possibility is that there is no good reason to condemn compassion, but you had better do it anyway, because Aiwass commands it.

You disagree with Aiwass—so do all of us. The trouble is that He can say: “But I’m not arguing; I’m telling you.” (Magick Without Tears, XLVIII)

But I am assuming for the sake of discussion that there is an argument in favor of the position. Crowley seems to agree, otherwise he wouldn’t have presented the argument in the first place.

While I consider it of service to others to show what Crowley said about this issue, why he said what he said, what I perceive to be possible responses to this issue, and what I perceive to be the likely consequences of those responses, I have made an effort not to tell anyone what the best response is. If it appears as though I have attempted to tell anyone what they should do, then that is the result of accident rather than design. It is ultimately up to each individual to decide this question (and all questions regarding Liber AL vel Legis) for themselves by appeal to Crowley’s writings (or however they see fit).