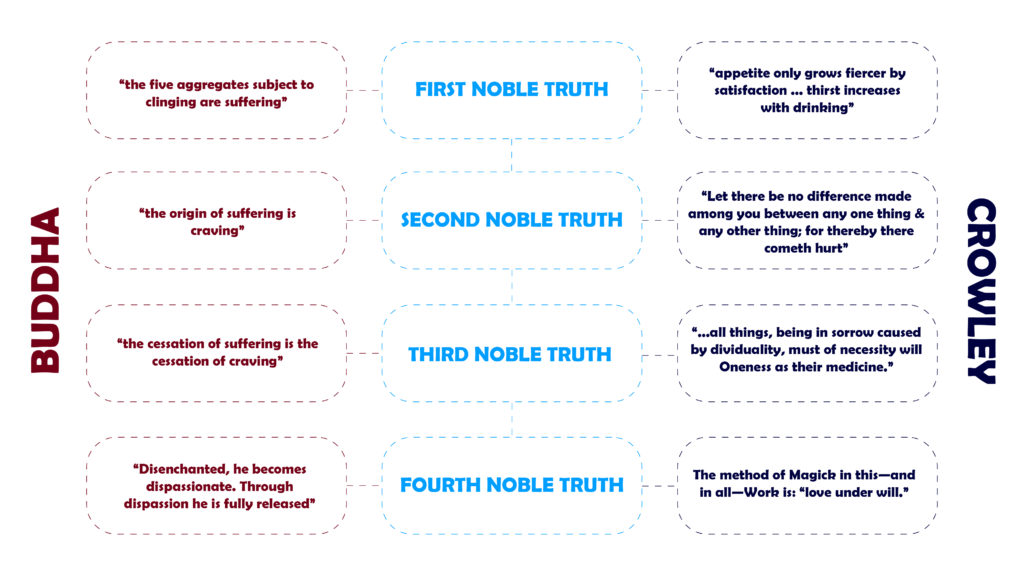

The first noble truth is often glossed as “all is suffering,” but that’s not what the Buddha said.

Now this, bhikkhus, is the noble truth of suffering: birth is suffering, aging is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering; union with what is displeasing is suffering; separation from what is pleasing is suffering; not to get what one wants is suffering; in brief, the five aggregates subject to clinging are suffering.

Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta

He’s explicit in the summary that it’s the five clinging aggregates that are sources of suffering, not existence itself. This is drawn out in the second noble truth.

Now this, bhikkhus, is the noble truth of the origin of suffering: it is this craving which leads to re-becoming, accompanied by delight and lust, seeking delight here and there; that is, craving for sensual pleasures, craving for becoming, craving for disbecoming.

Ibid.

In other words it’s the craving for the things, not the things themselves, that generates the suffering. If this weren’t true, if it were existence itself rather than the clinging or the craving that were causing the suffering, then there would be no way to achieve liberation in this life time. Becoming an Arahant would be meaningless, since one would still be embodied and experience aging and death. One would presumably have to wait until death to experience liberation. Instead it’s clear from the doctrine that while full liberation occurs at death (paranibbana) there is a kind of relative liberation that occurs in this life time. That’s the third noble truth.

Now this, bhikkhus, is the noble truth of the cessation of suffering: it is the remainderless fading away and cessation of that same craving, the giving up and relinquishing of it, freedom from it, non-reliance on it.

Ibid.

It’s interesting to compare this with Thelema, since there’s a lot of overlap in assumptions.

Following AL II.9, Crowley rejects the idea that existence is suffering. It is ultimately pure joy. But the Buddha also rejects the idea that existence in and of itself is suffering. In other words they both view suffering as based in conditions arising in the subject which can be overcome.

Like the Buddha, Crowley—folllowing AL I.44—views the resolution of suffering as depending upon the cessation of craving or lust. But how is that suffering to cease? For the Buddha, it depends upon understanding the true nature of the things lusted after—that they are impermanent and cannot provide lasting satisfaction—and thereby becoming disillusioned with them and ultimately dispassionate toward them.

Seeing thus, the well-instructed disciple of the noble ones grows disenchanted with form, disenchanted with feeling, disenchanted with perception, disenchanted with fabrications, disenchanted with consciousness. Disenchanted, he becomes dispassionate. Through dispassion, he is fully released. With full release, there is the knowledge, ‘Fully released.’ He discerns that ‘Birth is ended, the holy life fulfilled, the task done. There is nothing further for this world.’

Pañcavaggi Sutta

Crowley accepts the Buddha’s reasoning with regard to the fundamental impermanence of all conditioned phenomena, but he goes in the exact opposite direction from them that the Buddha goes. Instead of unconditionally retreating from all conditioned phenomena in favor of a purely transcendent unconditioned, the Thelemic path is an unconditional move toward impermanent, conditioned phenomena.

For see now how all things, being in sorrow caused by dividuality, must of necessity will Oneness as their medicine.

Liber CL, Part II

What Crowley is doing is clever. He’s not disagreeing with the Buddha when it comes to the fundamental nature of reality. The Buddha sees two possible attitudes of relating to this reality: one can either be lost in it, subject to craving, hatred, and ignorance, or one can dispassionately relinquish it. Crowley sees a third option: one can unconditionally unite with it.

Every operation of Love is the satisfaction of a bitter hunger, but the appetite only grows fiercer by satisfaction; so that we can say with the Preacher: ‘He that increaseth knowledge increaseth Sorrow.’ The root of all this sorrow is in the sense of insufficiency; the need to unite, to lose oneself in the beloved object, is the manifest proof of this fact, and it is clear also that the satisfaction produces only a temporary relief, because the process expands indefinitely. The thirst increases with drinking. The only complete satisfaction conceivable would be the Yoga of the atom with the entire universe. This fact is easily perceived, and has been constantly expressed in the mystical philosophies of the West; the only goal is ‘Union with God’.

Eight Lectures on Yoga, “Yoga for Yahoos: First Lecture”

This “Yoga of the atom [the individual consciousness] with the entire universe” is achieved upon crossing the Abyss and becoming a Master of the Temple, who “understand[s] the Universe perfectly [and is] utterly indifferent to its pressure.” (New Comment on AL II.9) For this reason Crowley is justified in regarding the Master of the Temple as the “Master of Sorrow” and equivalent to the Arahant. (See Liber B vel Magi and “One Star in Sight”.)

However, the methods are different. The fourth noble truth—the path to the cessation of suffering—is the noble eightfold path, which is a renunciate path. Craving is overcome by training oneself to see the downside of the things that one craves, starting with “gross” or sensual pleasures and moving toward more refined pleasures such as the craving for any change whatsoever.

By contrast, the path Crowley establishes to the cessation of suffering is not a renunciate path. One remains fully engaged with both gross and fine sources of pleasure or change; however, the training consists in not lusting after any particular change. Rather, one is to embrace every change, every event, equally, understanding it to be an expression of Self or “pure will”. Crowley refers to this spiritual path as “magick.”

These two paths—the renunciate path of Theravada Buddhism and the worldly path of Crowley’s Thelema—go in opposite directions from one another, but they end at similar places where one does not crave for any particular outcome. The Buddhist path ends in nibbana, and the Thelemic path ends in pure will, delivered from the lust of result (i.e., love under will).

But the phrase may also be interpreted as if it read ‘with purpose unassuaged’—i.e., with tireless energy. The conception is, therefore, of an eternal motion, infinite and unalterable. It is Nirvana, only dynamic instead of static—and this comes to the same thing in the end.

Liber II

They both involve the cultivation of dispassion. But while the Buddhist path can be thought of as an unconditional withdrawal from involvement in All, the Thelemic path can be thought of as unconditional embrace or acceptance of All.

This is important to understand. Thelema is not the assertion that existence is pure joy in the face of Buddhism or common sense. Crowley accepts at least some of the Buddha’s assumptions about the fundamental nature of reality. He just recognizes a way of dealing with that reality which the Buddha either wasn’t aware of or didn’t consider viable. It is the exploitation of this additional possibility—a path which Crowley eventually calls magick—that leads one to the realization that existence is pure joy. In other words, it’s not just an assertion or a little shift in attitude. It’s a training which is just as rigorous and demanding as the Noble Eightfold Path.