One idea I’ve moved toward over the course of the last week is that the Gnostic Mass can be seen as an object of contemplation.

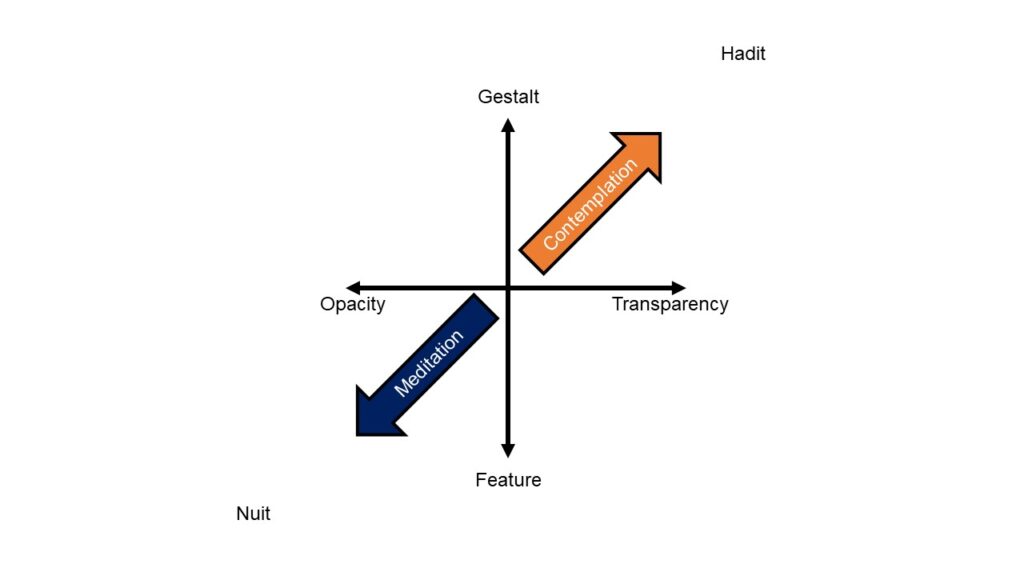

I understand the difference between contemplation and meditation along the same lines Jon Vervaeke does, as a relationship between the axes of Gestalt-feature and trasparency-opacity.

We can look at objects from the perspective of their features and the Gestalten the features compose. When reading a word, I can look at the individual letters (features), or I can look at the word (Gestalt). But nothing is inherently a feature or a Gestalt. While letters are features of words, words are features of sentences, and sentences are features of paragraphs. So it’s not either/or; there’s a continuum which is dependent upon context.

On the other hand, you can look at something (thereby rendering it opaque), or you can look through something (thereby rendering it more transparent). Think about a pair of eyeglasses. When you’re wearing them, you’re not conscious of them; you’re conscious of what you’re looking at through them. But should they become dirty, they become more opaque. When you take them off your face to clean them, they are even more opaque. They become conspicuous or “thematized” as the phenomenologists say. So there is a continuum of opacity and transparency just as there is with feature and Gestalt.

Plotting these two axes on a graph, we see how they interact. We can look through (transparency) our sensations out into the world to find patterns (Gestalten) there. We can pull back to look at sensations (opacity) thereby revealing more features and fewer patterns. The former is contemplation, the latter meditation (specifically vipassana). The former is scaling up of attention, the latter scaling down.

Symbols in general are objects of contemplation in this sense. They’re not meant to be looked at so much as looked through. They serve as lenses to look out into the world to perceive deeper patterns. (Words serve the same function, but symbols are different because they are more embodied. I’ve written about this before.)

So one of my theses about the Gnostic Mass is that it can serve as an object of contemplation in this sense. When we first encounter it, we’re mostly looking at it, but over time, we are eventually looking through it at the invariant patterns of reality. The patterns in this case are the theological truths of Thelema as described in the Creed.

Note how in the theology of Thelema, there is a limit to scaling up and a limit to scaling down. The upward limit is Nuit, and the downward limit is Hadit. This may seem an odd choice of phrasing, especially as Nuit in particular should be illimitable. I mean “limit” here more in the sense that it’s used in calculus than as a brick wall one runs into at top speed. “Asymptote” may give a better idea (Crowley liked thinking about them on analogy with transfinite numbers), but again, these are just more concepts one is meant to look through, not at.

Because the Gnostic Mass is, in part, a depiction of sublimated sexual reproduction, there’s also the potential for a top-down transformation (a rebound from Gestalt-opacity to transparency-feature). In other words the insight I acquire by looking through the symbolic representation of the act of reproduction then in turn sheds light on the act of sexual reproduction itself, highlighting a spiritual potential in it that was previously concealed. Similar things could be said about embodiment in general; magic is essentially tied up with the body and embodiment. The body is not just a lump of flesh opposed to spirit. It is the site—maybe the exclusive site—of the self-recognition of divinity.

This is how I understand the proclamation of the Priest and the congregants after taking communion, which itself is based on a line from The Proclamation of the Perfected One: “There is no member of the body of Asar which is not a member of God!”