My work is a critique of an already existing but unacknowledged dogmatic philosophy.

Questing for Truth and Goodness

We cannot fail to struggle with the meaning of truthfulness, courage, and justice without also failing at being human.

Cosmos, Critique, and Ideology: Reflecting on The Comment

A critical engagement with Thelema would require reading The Book of the Law against Crowley’s own interpretation—which would unambiguously contravene The Comment.

O.T.O. and Orthodoxy

There are two problems I see with the view that O.T.O. should not teach an orthodoxy.

Origin of the Kabbalists’ (and Crowley’s) first principle

The idea of “nothingness” as a creative first principle is often assumed to have an “eastern” (e.g., Chinese or Indian) origin. For instance, Pierre Bayle made this claim about the first principle of Kabbalah (Ain) in the 17th century, and Jacob Brucker made a similar claim in the 18th century. Recently I was saw someone remark that Crowley’s opening to the Book of Lies (“Nothing is – Nothing becomes – Nothing is not”) was “Taoist”.

Apparently the idea still has legs!

By Crowley’s own admission, he based his first principle on that of the Kabbalists, but the Kabbalists’ first principle is just the synthesis of two ideas which have been common in the west since antiquity. The first is the idea of creation ex nihilo, a power attributed (controversially) to the God of the Bible (see 2 Maccabees 7:28); the other is the idea that “nothing comes from nothing,” a formulation Aristotle gave to the Principle of Sufficient Reason (see Physics 1.8.191a28).

These ideas were usually seen to contradict one another. For example, Benedict Spinoza’s assertion of the latter principle was taken as proof of his atheism. (Though the aforementioned Pierre Bayle also used it as evidence in favor of Spinoza’s Kabbalism, even though Spinoza seems not to have had any interest in the subject.)

In his Historia Critica Philosophiae, Brucker noted that Kabbalah, “Oriental” thought, and Middle Platonism all shared in common the idea of nothingness as a substantive first principle. From this he concluded that both Kabbalah and Middle Platonism had origins in the east.

A half century or so later, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel discussed Kabbalah in his Lectures on the History of Philosophy. Interestingly his discussion of Kabbalah occurs in the section on Neoplatonism. He concluded that Philo of Alexandria’s philosophy already contained most of the presuppositions of Kabbalah.

A few noteworthy points:

- Hegel discusses Kabbalah in his Lectures on the History of Philosophy, not in Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion! He regards Kabbalah as philosophy, as do I.

- He recognizes—correctly, I think—that there is nothing necessarily “eastern” about Kabbalah’s first principle. There has been ample fuel in the west since antiquity for thinking of nothingness as a substantive first principle.

- He discusses Kabbalah—again, correctly—as a branch of Neoplatonic thought.

In other words, Hegel is noticing that the esoteric concept of creative nothingness comes from the Platonic tradition, not from Confucianism (as Bayle thought) or from Taoism (as some today have said).

Crowley of course assumes the exact same first principle as the Kabbalists. He even says, “I assert the absoluteness of the Qabalistic Zero.” If you’re looking for a constant in Crowley’s thinking, this was it. He asserts or implies it in Berashith, The Book of Lies, Magick in Theory and Practice, the Book of Thoth, Magick Without Tears, and—yes—the Book of the Law. (See AL I.46 inter alia.)

But Crowley didn’t get the idea from his encounters with eastern schools of philosophy. He states plainly where he got it from. He got it from the exact same place Bayle, Brucker, and Hegel got it: Kabbala Denudata, which Samuel Mathers translated into English in 1887 (with a lengthy introduction) and used as one of the bases of the work of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

Crowley didn’t just take this principle over, though. He applied it rigorously in a way I doubt Mathers ever did but which in some ways parallels Hegel’s use of it. And so it is infused throughout Thelema. Here’s just one example among many:

Thou must (1) Find out what is thy Will. (2) Do that Will with a) one-pointedness, b) detachment, c) peace.

—Liber II: The Message of The Master Therion

Then, and then only, art thou in harmony with the Movement of Things, thy will part of, and therefore equal to, the Will of God. And since the will is but the dynamic aspect of the self, and since two different selves could not possess identical wills; then, if thy will be God’s will, Thou art That.

The will is the dynamic aspect of the true self, Hadit. But Hadit is not the personality. Hadit is impersonal (i.e., indeterminate) identity. Another way to say “indeterminate” is “not-a-thing”. So to take up the standpoint of Hadit is to take up the standpoint of the first principle of Thelemic philosophy—but this is just the substantive nothingness which the Kabbalists called “Kether” or “Ain,” or God in His most esoteric form.

If the principle is essential to Crowley’s understanding of true will and his solution to the problem of determinism versus free will, then it’s obviously foundational to his thought in general.

Why a circular Tree of Life?

Reflections on the Path in Eternity (Part 4)

I came to magick via an unsual path: through my interest in the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

Hegel was not a magician. He was a late-18th/early-19th century philosopher in the idealist tradition (a branch of thought taking influence from Descartes, Berkeley, and Hume, but which is usually seen as having its origin with the Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant).

But it was after I had been interested in Hegel for over a decade that I read Glenn Magee’s book, Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition. (You can read the introduction of the book here for free. It actually provides a pretty good orientation for how Hermetism differs from Gnostism and traditional Christianity.)

Magee persuaded me that Hegel’s philosophy of Absolute Idealism owed at least as much to Renaissance Hermetism (or Hermeticism as it’s sometimes called) as it did to rational thinkers such as Hume or Kant.

Magee understands Hermetism as a broad spiritual current which has a theological basis in the Corpus Hermeticum but which also includes currents such as Qabalah, alchemy, and magic.

Pretty much everything we consider to be the western magical tradition has its origins in Renaissance Hermetism, in particular the synthesis given to it by Cornelius Agrippa. (Really the only component missing from Agrippa’s synthesis is the tarot.)

For more on this I highly recommend Frances Yates’s Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. Certain aspects of her work are considered controversial now. I recommend reading Copenhaver, Hanegraaff, and Kingsley alongside her.

One of the main impacts Magee’s book had on me when I read it is that—oddly enough—it legitimized occultism for me.

Hegel was a philosopher I had spent over a decade studying both in and outside of academia. I considered a lot of my philosophical intuitions to be “Hegelian”. The experience was a little bit like having lived in a house for several years and then one day discovering a secret sub-basement that wasn’t on any of the building plans.

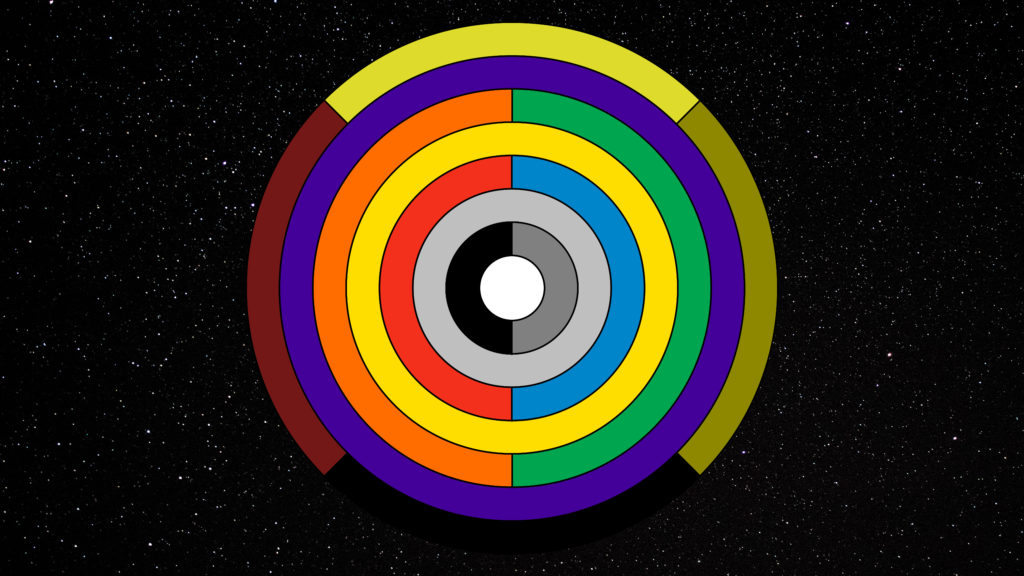

I was becoming familiar with the Qabalah right around the time I read Magee’s book (largely due to the work of my friend Daniel Ingram who also legitimized magick for me), so I recognized the Tree of Life in its usual top-to-bottom arrangement. But I was surprised to find out that there had been alternative arrangements of the sephiroth over time, including one in which they were presented as concentric circles.

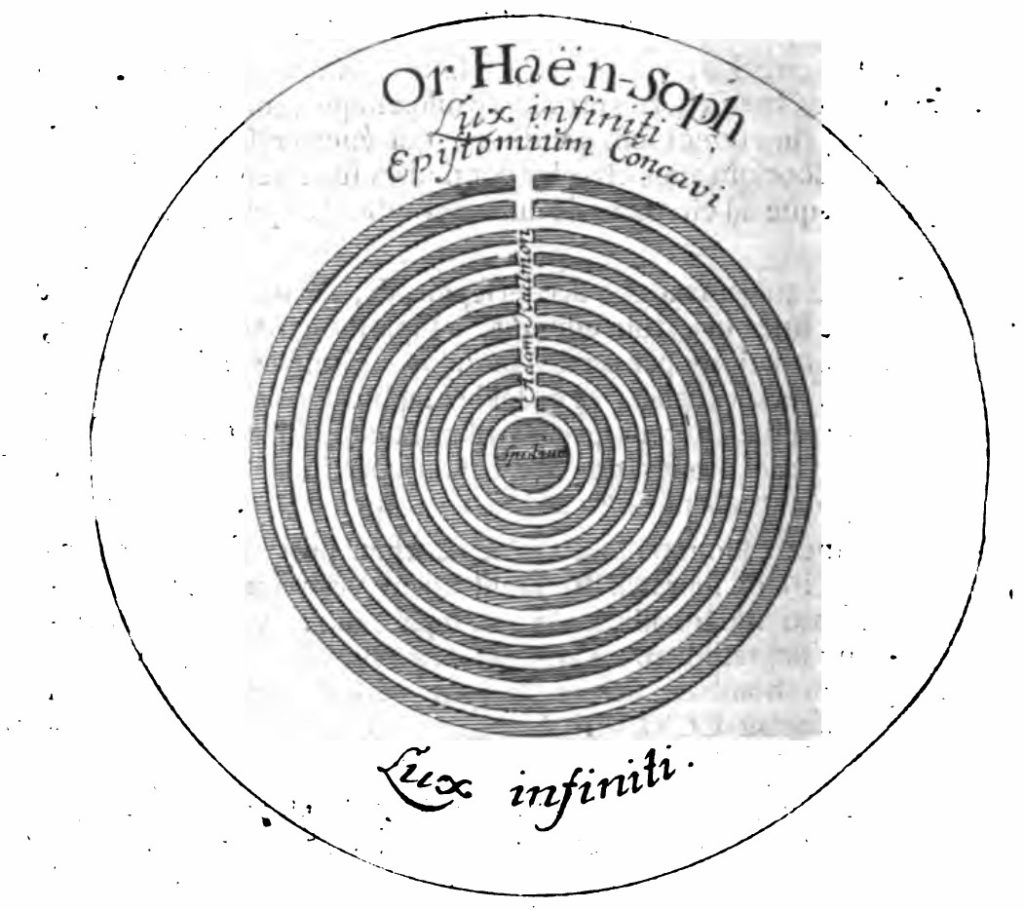

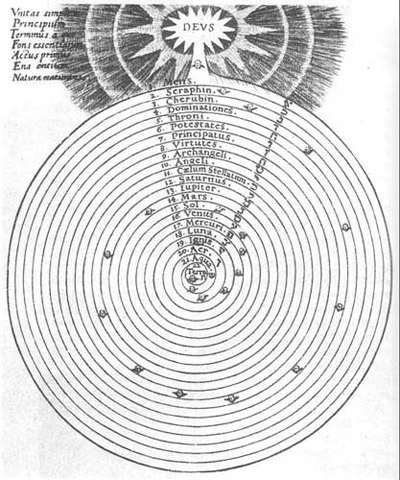

For instance, Johann Jakob Brucker gave them a circular arrangement in volume 2 of his influential Historia Critica Philosophiae (1742).

This diagram was Brucker’s attempt to illustrate a concept from the Lurianic tradition of Kabbalah, according to which each new act of creation or manifestation in the world is the result of a simultaneous contraction and expansion.

Isaac Luria and his followers envisioned the Ain Sof—the limitless infinity we previously identified with Nuit—as an infinite sphere in which a smaller sphere of empty space came into being through the tsimtsum, a primordial contraction or withdrawal of God.

It is into this empty space that God injects a ray of light which differentiates itself into the classical ten sephiroth. These were thought of as concentric circles of light filling the space within God created by the primordial contraction.

The first definite being that appears in the wake of the tsimtsum is Adam Kadmon (macroprosopus in the previous post). Adam Kadmon exists above the four worlds and mediates the light of Ain Sof into them.

Adam of the Bible—Adam Ha-Rishon—is an imperfect earthly embodiment of Adam Kadmon. While Adam Kadmon is spirit outside of space and time, Adam Ha-Rishon is spirit developing in nature, from the fall in the Garden of Eden and the loss of the immediate relationship to God, eventually to the recovery of that relationship in religion and mysticism (namely, Kabbalah).

(Ra-Hoor-Khuit is to Chaos as Adam Kadmon is to Adam Ha-Rishon.)

The implication of this concentric arrangement is that the material universe, individuals, and human history are not outside of the divine. Everything is in a certain sense “in” God. It’s just there in a corrupted or fallen state which has to be rectified over time.

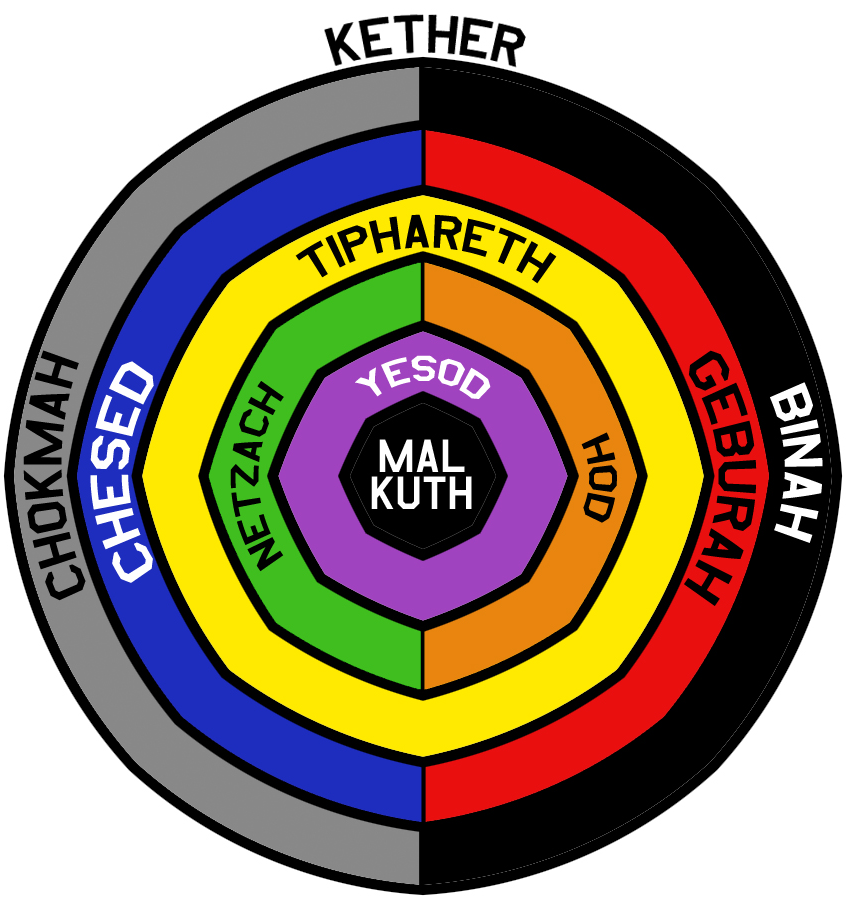

This sense of us being in God, of directly participating in the divine all the time whether we know it or not, can be occulted by the traditional top-down arrangement of the sephiroth, where it looks as though Kether, Ain Sof, and Ain are somehow way above us mere earthlings.

“A View from Kether” by IAO131

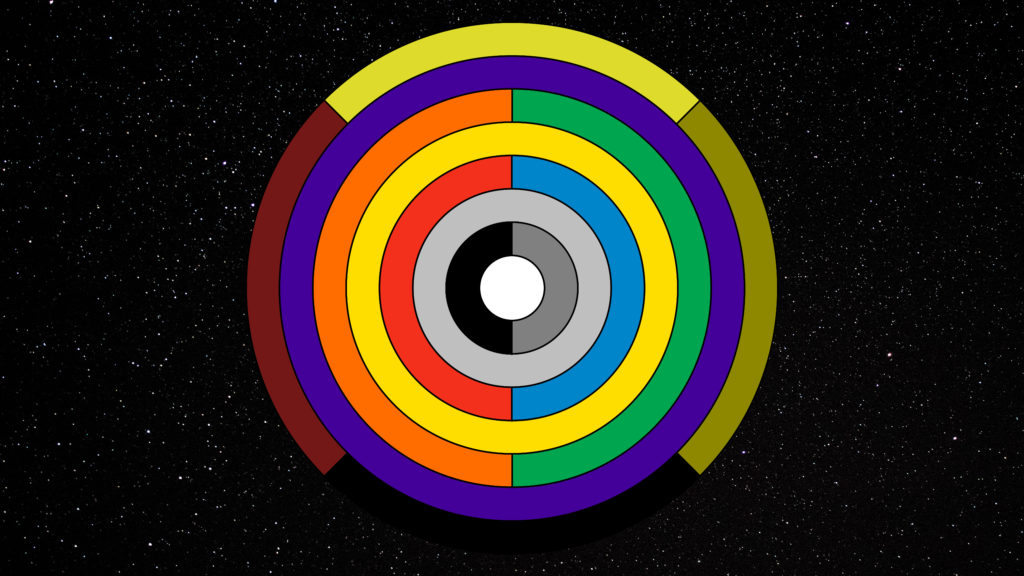

A few years later when I got into Thelema, I was pleased to see someone else had taken an interest in a similar arrangement. IAO131 created a diagram similar to Brucker’s in which Kether surrounds and contains the other sephiroth. My own version was inspired by his insofar as the sephiroth on the lateral pillars are depicted as semicircles rather than complete spheres.

What these concentric representations of the Tree of Life share in common is the implication that the reality we find ourselves in is one formed from an overarching, primordial, divine unity which divides itself.

There is some evidence in Crowley’s writings to support this view of our reality being the result of a self-division of God.

To know itself, each such Star, or Soul, must eat of the Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, by accepting labour and pain as its portion, and death as its doom. That is, it must reveal its nature to itself by formulating that nature as duality. It must express itself by a series of symbolic gestures ostensibly external to it, just as a painter reveals one facet of his Delight-Diamond by covering a canvas with colours in such a way that the picture seems at first sight to represent something outside himself. It must, in fact, repeat for itself the original Magick of Nuith and Hadith which created it.

New Comment on AL I.29 (emphasis mine)

AL I.29—of which this passage is a commentary—reads, “For I am divided for love’s sake, for the chance of union.”

We find in this passage echoes of the Lurianic idea of the fall as a temporary but necessary tragedy resulting from the diremption of an original, absolute whole (in this case the “Star, or Soul” of the individual).

The way to overcome this division is to repeat for ourselves the “original Magick of Nuith and Hadith” which created the star.

In this passage, Crowley presents the path toward liberation in artistic terms. The task is to see the world and the events in it, not as alien to our desires, but rather as vehicles for the manifestation of them. We are to view matter as (akin to) artistic medium.

The world loses its alien, painful character when it is understood and willed. When we can see the world as our own artistic creation, we have achieved liberation.

This is an interpretation of the Thelemic path of liberation I explored in my talk on the Magical Power of Art.

It was with something like this in mind that I formulated my own version of the concentric Tree of Life. However, unlike Brucker or IAO131, I reversed the order of the sephiroth. Rather than having Kether on the outside and Malkuth in the center, Malkuth is on the outside and Kether is in the center.

As it turns out, my reasons for doing this are numerous and complex. But before explaining any of them in detail, it’s worth mentioning that old adage that “the map is not the territory.”

I don’t believe sephiroth literally exist, let alone whether they are really, in any kind of metaphysical sense, related to one another externally or internally, or whether Malkuth can really be said to be at the center or not. That’s not really the point of a diagram.

In this context, the purpose of the diagram is to serve as a heuristic. It’s an attempt to convey some complex ideas in a simplified format that makes them easier to comprehend.

There could well be certain aspects of Thelema that are better captured by having Kether on the outside and Malkuth in the center, just as there are aspects that are better captured by the usual hierarchical (top-down) arrangement.

All of that being said, there are a lot of spiritual, metaphysical, theological, and soteriological assumptions packed into this simple decision to put Kether at the center and Malkuth on the outside.

Some of them require a lot of explanation and carry with them a lot of implications, so rather than go into any of them in depth right now, I’ll just list them succinctly.

- Repeat = Defeat. Let’s present something familiar in an unfamiliar format to discover new things about it.

- The journey is inward, out outward. Crowley described the work of A∴A∴ (in contrast with the work of O.T.O.) as a process of going inward toward the three supernal sephiroth. Without taking it too literally, that implies a certain spatial relationship. And since all the sephiroth are to be found “in” Malkuth, this links Thelema with what might be termed a chthonic counter-current in Western mysticism.

- The Khabs is in the Khu, not the Khu in the Khabs. Again, this implies a particular spatial relationship. This also implies that divine reality is not some original whole we were cut off from and have to get back to. This core spiritual idea sharply differentiates Thelema from Hegelian Idealism, Gnosticism, or even from Kabbalah. In Thelema the individual really is primary and irreducible in a way that you just don’t find in those other traditions.

- Thelema is about 2, not about 1. It’s all about the relationship between Hadit and Nuit. In order for there to be a love relationship between Hadit and Nuit, Nuit must be other than Hadit. That doesn’t work if Hadit and Nuit are merely parts of a primordial, original whole.

- It’s all about the going. Experience matters. Change is real. It is powerful, it is divine, and it is meaningful. The O.T.O. teaching on the Path in Eternity is as central to Thelema as are the teachings of A∴A∴ on the Holy Guardian Angel and the Abyss.

- It’s magick, not just mysticism. Going implies change, change implies magick, magick implies the Will. Willing implies traditionally masculine qualities such as mastery, overcoming, and expansiveness in addition to the feminine characteristics of dissolution and surrender that are particular to mysticism. Both sides are necessary for a complete understanding of Thelema.

I don’t know yet if I’m going to write posts about all of these. If there are particular ones you definitely want to hear about, though, let me know in a comment.

Yoga and eroticism in the Platonic tradition

The Good and the One in Proclus

The highest principle in Platonism is the Good. The identity between the Good and the One is established by Proclus in the 13th proposition of his Elements of Theology.

All that is good is the unifying principle of its participants, and all union is good, and the Good is the same with the One.

For if the Good is the preserving principle of all beings (for which reason it is also the object of desire for all), but that which is preservative and connective of the essential being of every being is the One (for all are preserved by the One and dispersion removes every being from its essential being).

For the Good completes and contains those, in which it is present, according to one union.

And if the One is collective and connective of beings, then it will perfect every being by its own presence.

Accordingly then, it is also Good for all these to be united.

Proclus, Elements of Theology, Proposition 13

The argument is extraordinarily terse, so it merits unpacking. But the unpacking will not only tell us why the Good is also the One but also what the characteristic function of the One is such that it is good.

Starting with the second paragraph, Proclus argues from the Good to the One by means of the way in which the Good preserves and connects the “essential being of every being” that participates in it.

So to the extent to which something participates in the Good, it is moving—through time—toward a state in which it is more exactly what it in essence is. In other words it is moving toward perfection. And the extent to which it is moving away from the Good, then over time it is decaying or falling away from what it is.

The principle way in which the Good allows beings to be what they essentially are is through its “preservative and connective” function. In other words, it accomplishes this by making and keeping them whole over time.

To put it another way, all material things are composite and subject to change. If the component parts of something fly off in all directions, the thing is destroyed. But to the extent to which the parts maintain their proper connections with one another, the being of which they are parts maintains its unity, its wholeness. But wholeness or unity as such is the One, and therefore the Good is also the One.

And then he runs the argument the other way in the fourth paragraph. The function of the One is “collective and connective”. To participate in the One is to experience greater unification with oneself, a greater degree of wholeness, and so one moves toward perfection or being what one in fact truly is. But we already know that this is what participation in the Good rewards one with, and so the One is also the Good.

Proclus’s argument relies upon the preservative and the connective functions of the Good and the One.

He assumes that the Good is the preserving principle (sostikon—from sozo meaning salvation) of all beings, and that the One is the preservative (sostikon) and connective (sunektikon) principle of the essential being (ousia) of every being. By virtue of the preserving and connecting, all are preserved (sozetai—again, “saved”) by the One.

This is important not only because it is the fulcrum around which Proclus’s argument turns, but it also gives us insight into the essential nature of the One and how it functions. We might say the highest ontological principle in Platonism is a principle whose main function is to bring about preservation or “salvation” (sostikon) by keeping together (suntereo) or by synthesis (suntithenai).

Logos and Synthesis

Probably the most famous modern proponent of a “synthetic” ontology is the philosopher Immanuel Kant. Kant famously declared all principles of metaphysics (of which ontology is a part) to be synthetic a priori. This means that such propositions must be justified independently of empirical experience, but that they also cannot be justified solely by the meaning of the terms involved. An example of such a synthetic a priori statement for Kant would be, “Every event has an antecedent cause.” There is no way to prove such a statement on the basis of examining particular occurrences, but it is also not possible to derive the term “antecedent cause” from analysis of the dictionary definition of “event” which just means “change from one thing to another.”

The way in which Kant proposes to justify synthetic a priori propositions—and hence provide a secure foundation for metaphysics—is by grounding them in subjective processes of the mind which are nevertheless necessary for having any empirical experience at all. Kant argues that there are certain rules of experience which are not derived from experience but which the mind structures experience in accordance with. In other words, the underlying logical architecture of the mind necessitates that sensations be connected with one another in certain ways, and one of these ways in which the mind connects things is according to the rule of cause and effect.

To put it another way, logic projects semantics on to the world. And the way Kant argues the mind projects its meaning on to the world is through a process he terms synthesis.

(At this point, with the subjectivizing of synthesis and the world-building function, we are closer to the Thelemic understanding of these categories than the Platonic understanding.)

Our English word logic derives from the Greek word lógos, which means “speech, oration, discourse, quote, story, study, ratio, word, calculation, or reason.” The Greek word for “I speak” is légō. Both terms are derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *leg- which means “to collect, gather.”

So in the Greek word for speech we have the idea of collecting or of synthesis—the same function Kant assigned to the underlying architecture of the human mind and the same function which is so crucial for understanding the One in the Platonic tradition.

So we might go a step further in our explication of the One and say that, while its essential functions are connecting, keeping together, and preserving/saving, this essential function is carried out, or is in fact identical with, a kind of speech.

To put it somewhat differently, the One projects a “logic” on to beings—let’s call it an invariant cosmological structure or set of laws—but rather than this logic subsuming beings or somehow fixing them into place, it has the seemingly paradoxical effect of “saving” them (from decay) in such a way that they are allowed to go on to be precisely what they are in their essence (ousia).

To say it yet another way, this time in more explicitly theological language, divine logos—a power which the Hermetic tradition assigned to Thoth-Hermes and called the Second God or the Son of God—frees things to be what they are in themselves.

Eros and Divine Logos

In the Orphic Hymn to Aphrodite, we find the Greek goddess of beauty and love described as “she who causes beings to mate” (zeukteira—from zeuktēr, “one who yokes”). A couple of lines later, she is described in the same way, this time with regard to the cosmos itself: “and you have caused the cosmos (kosmon) to couple (upezeuxo)”—literally, you have “yoked” the cosmos.

The Greek word for yoke is zugós, which comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *yugóm, which means to join. This is the same root from which derives the Sanskrit word yoga, which also means yoke or union and which eventually acquired the connotation of union with the divine.

So in the poem we see Aphrodite described according to two functions. She “yokes” mortal lovers together—i.e., she causes them to fall in love and to mate—and she also causes the cosmos itself to couple or to join. And it’s clear from the play on words in the Greek that the author intended for the mind to associate the one function with the other.

But we have already seen that joining and connecting—especially when looked at from the cosmological or metaphysical perspective—is the function of the One. Not only that. It is the essential function of the One and also that which makes it the Good. To speak of Aphrodite as serving as cosmological matchmaker, therefore, is to endow her with the power of the One, the highest ontological principle. In fact it is to say that she is identical with the One.

Looked at from the other side, we might say that in addition to its ontological and “logical” functions, the One also has an erotic function. In other words, our account of the way in which the One “connects and preserves” through “speech” is incomplete unless we also understand this connecting and joining from an erotic and conjugal perspective.

To be clear, I am not saying that the One is in fact Aphrodite. I’m claiming two things. (1) There is an erotic dimension to the characteristic activity of the One. As a mnemonic, one might represent that function by the Greek goddess Aphrodite in the same way one might represent the logical function of the One by the Greek god Hermes. And (2) we should be careful forcing a separation between erotic love and spiritual love. Eroticism is not mere carnality but has a hieratic potential. We will explore this potential in depth in the next section.

Finally, when we speak of something being something, we can say this in many different ways. For example, we can say that it is, i.e., that it exists, but we can also assign a predicate to it, e.g., “The horse is fast.” The predicate is fast is not identical with that which is identified by The horse—it is different—but it is joined with it through the function of the verb to be. But by joining this general concept fast with the particular horse, we are in fact revealing something essential about the horse itself, viz., that it is fast. So again, somewhat paradoxically, by going away from the horse itself to something other than the horse, we do not turn away from or cover over the horse but instead reveal something true about the horse itself.

This function of the verb to be, when it joins a predicate with a subject, is called the copula. It comes from the same root from which we get the English word copulate. Something of the erotic dimension of logic and ontology is captured in our using that particular word to describe predication.

Love and Liberation

One of the things we were at pains to emphasize earlier is that participation in the One does not efface beings. To realize that “all is one” is not to see all things as the same thing. In fact the One is not a thing at all, and so participating in the form of the One does not reduce all things to the same thing. Rather, it frees beings—saves them in the language of Proclus—to be what they essentially are in themselves as self-unified beings. Insofar as it makes sense to speak of the One projecting a kind of logical structure on to beings, the purpose of this structure is not to ensnare or enclose them but paradoxically to release them into their ownmost being. They are released to the world, but more importantly, they are released to themselves and in a sense to their own care. We can now refine this conception in light of the teaching of “Orpheus” by saying that this joining-freeing is also divine loving.

From the perspective of ontology and cosmology we might say that the Platonic doctrine of the One as developed by Proclus is in some ways quite similar to “eastern” cosmologies, particularly yogic or “tantric” conceptions according to which the phenomenal universe is the result of the sexual union of Shiva and Shakti, or lingam and yoni.

From a soteriological point of view we might say that there must be a tight association between (a) knowing oneself, (b) that direct knowing of God which the Greeks called gnosis, and (c) eroticism. The One joins disparate things together to become whole beings in what we might term cosmological marriage or coitus. But in the case of a human being, knowledge forms part of that whole. So to achieve perfection or union entails the power of the individual not only to turn back on their self but to also know that they are turning back and to know precisely what it is they are turning back on. In the case of a conscious being, the reflection is explicit, willed, and clear. So the perfection of the individual entails what Hegel may have termed the satisfaction of self-consciousness. But as we saw at the beginning, to move toward perfection and to participate in the Good are identical. Hence, knowing oneself and knowing God are identical.

The erotic dimension of salvation enters when we recognize the yogic dimension of self-unification. To gather oneself together into a singular awareness is what is termed in the Pali Buddhist tradition ekaggatā or one-pointedness. It is one of the factors of samādhi or meditative absorption. Other factors include píti (rapture or joy) and sukha (happiness). The joy and happiness attendant upon samādhi are subtler than “gross pleasures” but they are more enduring and more reliable, and hence in the context of Theravada Buddhism, samādhi is considered to be an important intermediary set of experiences between ordinary consciousness and complete awakening.

There is a similar intermediate experience described in the Platonic tradition between ordinary consciousness and direct knowledge of the One, which Plato in the Symposium describes as the idea or the form of beauty. In the experience of the form of beauty, it is linked with justice and goodness, and—most importantly—it is apprehended as the principle of unity itself.

I don’t think that Plato means to reduce the One to the experience of beauty. More likely he intends the idea of the beautiful to be an apophantic quality of the One: something like the closest correlate to the One that one may encounter by means of sensation. (The Greek word for sensation is aisthēsis from which we get our word aesthetics.) It is possible that by the apprehension of the idea of the beautiful Plato has in mind an experience not very different from that of samādhi in the Buddhist and Hindu traditions.

If that is the case, then the Platonic spiritual path might be said to consist in the pursuit of deeper and more profound experiences of beauty until apotheosis occurs. The path described in Symposium is one in which the soul progresses from coarse beauty to ever more refined forms of beauty, until one moves from loving beautiful things to craving Beauty itself. The Platonic spiritual path is therefore equally an erotic and aesthetic path of liberation.

Implied in the Platonic spiritual path is a challenge to the idea that we can cleanly separate erotic love and spiritual love. As Plato illustrates in Symposium, the first pursued deeply enough leads to the second.

It is now clear that adequately understanding erotic love can lead us to a direct experience of Beauty and then the One. But is there anything that our experience of Beauty and the One can teach us about erotic love? In other words, how should spirituality inform our romantic and sexual relationships?

Between the Romantic and the Divine

It seems to me one might construct a “Platonic” approach to sexual and romantic relationships along the following lines.

Normally when we use the phrase “Platonic love,” we mean mere friendship. While much of what I will say applies to friendship, I don’t mean friendship exclusively. I also and primarily mean romantic and sexual love relationships. With that in mind, I would suggest the following principles:

- We don’t necessarily fall in love with people who are good for us. We just tend to fall in love with people who are familiar. If your upbringing was wonderful, you’re one of the lucky few who are perhaps attracted to people who are also good for you. For the rest of us, read on!

- Look for someone you admire. Find someone with admirable qualities, someone you can look up to. Find someone who at least some of the time models what you consider to be good in the world. This applies to all relationships, not just romances.

- Find someone who wants what is best for you and in you. You want a person who is happy for you when you’ve achieved something meaningful and who will be there for you when you’re going through a rough time. Avoid people who are envious of you or who are resentful of your happiness as much as possible.

- Understand that the relationship itself is prior to the individuals composing it. What I mean is that you are not in charge in the relationship, and your partner is not in charge in the relationship. The relationship itself is in charge. When you have a difference with your partner, the “winner” is the person who wants to do what is best for the relationship. This is because:

- A relationship is more than the sum of its parts. It has to be, otherwise we wouldn’t bother with them. If we could get what we needed by ourselves, for ourselves, we wouldn’t bother with relationships. The whole point of a relationship is that it can provide for you in a way you cannot immediately provide for yourself. You ruin this power of a relationship when you just try to get things for yourself. Make the relationship healthy, and you can get so much more than either of you could get just trying to be selfish.

- At its deepest level, a relationship is a spiritual entity. It is a logos. It has a certain intelligibility and wholeness all its own. It is a living being. Like the One itself, the purpose of the relationship is to unite its component parts (the individuals in the relationship) through love and to bring them to fulfillment and wholeness in themselves. So do not consciously devote yourself to your partner. Consciously devote yourself to the partnership, and by its divine power it will unite the two of you.

- Investing in the third entity, the partnership, can mean a lot of things, but much of it comes down to fairness and reciprocity. You give freely of yourself to your partner because you know they will do the same thing for you. This frees you of self-obsession and brings freedom and well-being. This isn’t just based on Platonic theory; it also seems to be based on biology. Stan Tatkin has written a few books about this which you may want to check out. The “spiritualizing” of it is mostly mine, though.

What is at stake between mysticism and rationality?

It strikes me that Plato’s philosophy derives at least in part from the recognition of how bad the consequences of civil and political unrest can be. He lived through the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War and saw first-hand what happens when tyranny and demagoguery gain the upper hand. This explains in part why he rejected the mysticism of Parmenides in favor of being able to give a clear account of shared reality. He saw for himself what happens when everyone has their own reality and words mean whatever people want them to mean. The picture wasn’t pretty.

Hermetism and Gnosticism, by contrast, were Pax Romana philosophies. They bear a superficial resemblance to Platonism, but really they are about individual, ineffable experiences of ultimate reality. As the Roman Empire falls apart, these individualistic, mystical philosophies are upstaged by Catholicism with its emphasis on the Christian Church, not the individual, as the basic unit. Hermetism and Gnosticism eventually experience a resurgence, but only under the protective umbrella of Medici mercantile wealth and a sympathetic Borgia Pope.

To put it another way, Plato did not seem to take peace for granted. Peace requires negotiation, and negotiation requires language which is able to give an account of shared reality. We don’t just stare in wide-eyed wonder at the truth; we have to be able to bring back an account. Most of Socrates’s interlocutors experience this responsibility as an imposition, as do many of the privileged today. But Plato grasped that to be freed of this burden did not lead to individual freedom any more than being freed of air resistance allowed a bird to soar. The opposite of rationality is not individual expression; it’s just violence.

Between Rationalism and Fanaticism

In my opinion what makes Thelema distinctive is not the occultism, not the ontology, not the ethics, not the individualism. It’s that he took the western occult tradition with its God as a creative artist and inflected it through a Nietzschean understanding of life.

Renaissance occultism is based upon a view of the cosmos where everything is ordered into spheres or levels with Earth as the focus. Natural magic is about drawing power or spiritus down from higher spheres into lower ones. “Cabalistic” magic is about ascending to superluminary spheres and mastering the angelic forces there—which tips over very easily into mysticism, as it does in Thelema. In short it’s based on a hierarchical, anthropocentric view of the universe as a kind of container focused on human affairs, and the container is overall not that large.

This view was largely replaced by the natural philosophy in the 17th and 18th centuries. According to this new view, the universe does not behave according to purposes but rather mechanisms. There are no “pulls” in the universe, only “pushes”. And the universe in which these abstract mathematical laws operate is vast enough to overwhelm the imagination and the human perspective all together. The picture of the universe generated by this natural philosophy ultimately left up in the air the place of humans in it. And with this disenchanted view of nature came a challenge to both religion and magic.

Rather than recoiling from this picture of nature into a kind of reenchanted fantasy about life, Crowley instead embraces it. The sheer enormity of the cosmos is one of the premises of Crowley’s view of reality, embodied in the goddess Nuit. The pure mathematical view of reality is not rejected either but embraced. Mathematics was part of occultism going back at least to Pico, but Crowley really makes it one of the main themes of his spirituality. So in other words rather than trying to hide from the implications of modernism, Crowley leans into them.

And he understands the fundamental spiritual problem in a very modernist way. The problem we face is not suffering, and it’s not ethics. These are pre-modern or early modern ways of looking at the problem. No, the main problem is meaning. It’s the senselessness of the world. Crowley was motivated by this experience of senselessness at least since he was a student at Cambridge, and he writes about it at least as late as Little Essays Toward Truth.

What then determines Tiphareth, the Human Will, to aspire to comprehend Neschamah, to submit itself to the divine Will of Chiah?

Aleister Crowley, Little Essays toward Truth, “Man”

Nothing but the realisation, born sooner or later of agonising experience, that its whole relation through Ruach and Nephesch with Matter, i.e., with the Universe, is, and must be, only painful. The senselessness of the whole procedure sickens it. It begins to seek for some menstruum in which the Universe may become intelligible, useful and enjoyable. In Qabalistic language, it aspires to Neschamah.

The way he understands a possible solution to senselessness is very modernist as well. The solution cannot be sought in reason. Reason operates according to the principle of sufficient reason, i.e., for any proposition F, there must be a ground G for it, or for any event B, there must be a sufficient explanation A. Putting the principle of sufficient reason at the center of human relating to the world is what generated the picture of a senseless, purely mechanical world in the first place. Therefore, reason—specifically the application of the principle of sufficient reason—must be limited, but to limit reason it must be transcended.

But—the transcendence of reason cannot interfere with the legitimate operation of reason within its own domain. Crowley is not looking to reenchant nature in some naive way. He accepts the findings of the scientific view of reality and even holds them to be axiomatic for his spirituality. Nor can the transcendence of reason be a mere animalistic “overcoming” of reason. One cannot simply will oneself to be irrational, for instance. Both of these avenues would represent a kind of fanaticism.

So Crowley has to manuever somehow between the Scylla of rationalism on the one hand and the Charybdis of dogmatism or fanaticism on the other.

This is a very modernist—specifically German Idealist—way of looking at things. When a person with a background in the philosophy of Kant, Fichte, Hegel, and Nietzsche hears Crowley talking about transcending “because,” they’re hearing a tune they could hum in their sleep.

And Crowley’s proposed solution to this problem is will. Will transcends reason. You cannot ask “why” of will. In and of itself it prevents the questioning but instead gives orders. It’s authoritative. This is how he avoids rationalism.

But will also represents the “true” self of the individual. It is not a mere replacement for Jehovah. It is not a projection of the law of the father. Nor is it exactly bodily or animal instinct. This is how Crowley avoids fanaticism.