Levi’s lucid account of the Four Powers of the Sphinx provides us with the groundwork for a training in virtue as propaedeutic to the study of ceremonial magic.

Magic and Macrocosm

One of the distinguishing features of ancient magic is the view of the universe as a living whole in its own right: what is called a “cosmos” or a “macrocosm”. Things are not just mechanically related to one another but tend toward higher purposes, the highest of those purposes being the metabolism of the whole.

There are no isolated individuals in such a world. We are all organs of this more fundamental cosmic organism—or, if you prefer, of a divine order of things. The magician plays a special role in this divine order. They are not simply a miracle-worker or healer. They are also responsible for assuring that the divine is firmly anchored in this world, so that the cosmological metabolism may continue.

One implication of this is that not just anyone can become a magician. Magic is not principally a set of techniques you pick up and apply to an otherwise pliable substrate. One must be selected for such work. The work itself cannot be carried out just as one wishes—unless one wishes to offend the gods. Another implication is that one experiences the macrocosm as an undeniably vast, awesome, even terror-inspiring entity that dwarfs the individual—and yet at the same time, there is the recognition that we are somehow essential to this whole. Without the magician there to anchor the divine in this world, the divine would not exist.

Crowley’s idea of true will could be viewed as an attempt to reestablish this ancient idea on a more modern footing. The true will of a person is not their freedom of choice to do this or that. That’s what Crowley calls “do what you want”. Your true will is the role you are predestined to play in the universe. It’s your karma, which means that it is irreducibly relational. There is no meaning to your will outside of the particular way of relating with the rest of the universe and the other stars in it—meaning, there is no way to get rid of “accidents” such as embodiment, the family and culture you happen to be born in, the state of the country and the world you find yourself in, and all the problems of human relatedness. All of it needs to be worked with skillfully, a work Crowley generalized with the term “magick”.

This is why Crowley says you have to discover your true will, accept it, and live in accordance with it, not attempt to invent it. It’s the attempt to invent ourselves according to preconceived ideas of what a person should be that leads to all the trouble in life. Instead you need to learn the nature and powers of your own being and how they express themselves in relation to the rest of reality, and learn to serve that microcosmic function to the best of your ability.

The attempt to jettison the macrocosm and to make magic all about “doing MY will” (as though “I” own the will rather than the will owning or expressing itself through “me”) in abstraction from a higher, preordained purpose—or the attempt to define “truth” purely in terms of what I find “useful”—is basically what Crowley means by the Left-Hand Path. The person who follows that path of radical individualism or subjectivism abstracted from the purpose of the whole is the Black Brother, who is the antithesis of the Saint. The Black Brother thinks they have a will; reality is what they will it to be. The Saint has come to understand the reverse: the will has created a temporary, imperfect self so that it may experience the perfection of existence. The Saints understands themselves as instruments of that higher reality.

The Two Foundations of Thelema

One of the most prevalant memes within Consensus Thelema is the idea that Crowley changed his mind so many times on so many different issues, it’s pointless to try to isolate any invariant “truth” within his thought. (Therefore it’s up to each individual to define for themselves what Thelema is blah blah blah let’s open another bottle of Apothic Red.)

But Crowley wasn’t that much of a creative genius. He had two insights, one theoretical, one practical.

The theoretical insight comes from the Kabbalah, mainly Samuel Mathers’s “Introduction” to Kabbalah Unveiled, his translation of Kabbalah Denudata. In particular, Crowley takes the idea of Ain, makes it the centerpiece or first principle of his world outlook, and draws implications from it that Mathers himself didn’t seem very interested in but which are reminiscent of how this idea was received in German language philosophy of the previous two centuries. By the time Crowley seriously engages with eastern philosophy, he has this Ain idea firmly fixed in his head, and he has a tendency to conform eastern philosophy (particularly Taoism) to it.

The practical insight—what I have called erotic liberation—probably comes from the fin de siècle decadent movement. It’s already on display in his 1898 poem, “Jezebel”. There you can see the mix of sadomasochism, cannibalism, and destruction (moral and physical) through eroticism that comes to define a lot of Crowley’s own spiritual praxis.

The practical insight probably precedes the theoretical insight, although the spiritual importance of the practical side lies in the fact that it reveals or discloses the first principle which organizes the theoretical side. In other words, Crowley may have insisted upon a mathematical deduction of his first principle in “Berashith” and Magick Without Tears, but neither mathematics nor reason in general are the main means by which one encounters the first principle in its fullness. That only comes about through the ecstastic practices Crowley eventually calls magick.

These ideas were formed whole in Crowley’s mind by the time he was 25 or so. Anything he encountered after that, he tended to wrap around or conform to these ideas.

As an aside, this is why it’s wrong to treat Thelema as a mere appurtenance to ceremonial magick, as though Thelemic magick is basically Golden Dawn ceremonial magic but done with a badboy attitude. While drawing shapes in the air and mispronouncing Hebrew are certainly aspects of the Thelemic magical tradition, that’s not the center of gravity of Thelemic praxis. One would be closer to the mark emphasizing transcendence through the encounter with potent (sexual) disgust—through the Pe in particular.

Heliocentrism and Hermetism

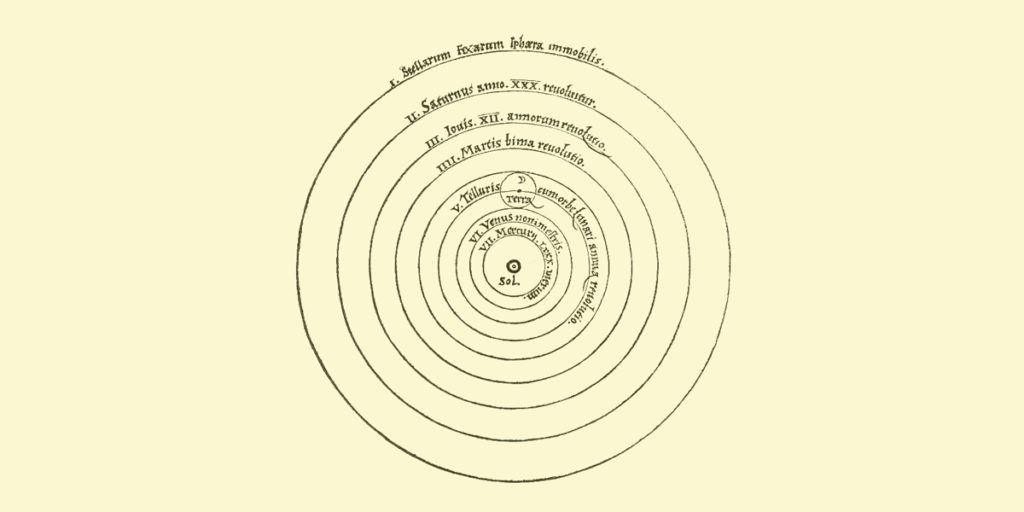

One of the ideas Frances Yates explores in Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition is the intersection between hermetism and heliocentrism.

I said a little while back that the hermetic universe was small and geocentric, which couldn’t be more wrong. Giordano Bruno in particular was really excited by heliocentrism. He felt it marked a spiritual shift and signaled the revival of the true ancient Egyptian religion which was oriented toward the Sun as the Second God or demiurge.

He also grasped the significance of heliocentrism for the size of the universe. If the Earth is in motion, but the background of stars does not appear to move, then that implies that the stars are much further away than people once thought. This was an enormous shock to people in the 16th and 17th centuries, as the revealed universe dwarfed the human perspective.

Bruno viewed himself as the prophet of this new spiritual dawn, which entailed the moral and religious reform of mankind.

In 1919 Charles Stansfeld Jones published an essay in Equinox III:1 called “Stepping out of the Old Aeon into the New” in which he said, “The Sun does not die, as the ancients thought; It is always shining, always radiating Light and Life. Stop for a moment and get a clear conception of this Sun, how He is shining in the early morning, shining at mid-day, shining in the evening, and shining in the night. Have you got this idea clearly in your minds? You have stepped out of the Old AEon into the New.”

But in his De Umbris Idearum of 1582, Bruno had already pointed out that the intellect does not cease to illuminate, and the visible sun does not cease to illuminate, just because we do not turn towards it. He intended this in a spiritual and not primarily physical sense.

The “New Aeon” was inaugurated in the 16th century, and its prophet was Bruno, not Crowley.

Between Rationalism and Fanaticism

In my opinion what makes Thelema distinctive is not the occultism, not the ontology, not the ethics, not the individualism. It’s that he took the western occult tradition with its God as a creative artist and inflected it through a Nietzschean understanding of life.

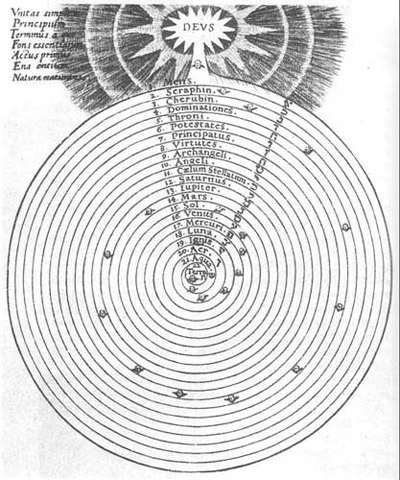

Renaissance occultism is based upon a view of the cosmos where everything is ordered into spheres or levels with Earth as the focus. Natural magic is about drawing power or spiritus down from higher spheres into lower ones. “Cabalistic” magic is about ascending to superluminary spheres and mastering the angelic forces there—which tips over very easily into mysticism, as it does in Thelema. In short it’s based on a hierarchical, anthropocentric view of the universe as a kind of container focused on human affairs, and the container is overall not that large.

This view was largely replaced by the natural philosophy in the 17th and 18th centuries. According to this new view, the universe does not behave according to purposes but rather mechanisms. There are no “pulls” in the universe, only “pushes”. And the universe in which these abstract mathematical laws operate is vast enough to overwhelm the imagination and the human perspective all together. The picture of the universe generated by this natural philosophy ultimately left up in the air the place of humans in it. And with this disenchanted view of nature came a challenge to both religion and magic.

Rather than recoiling from this picture of nature into a kind of reenchanted fantasy about life, Crowley instead embraces it. The sheer enormity of the cosmos is one of the premises of Crowley’s view of reality, embodied in the goddess Nuit. The pure mathematical view of reality is not rejected either but embraced. Mathematics was part of occultism going back at least to Pico, but Crowley really makes it one of the main themes of his spirituality. So in other words rather than trying to hide from the implications of modernism, Crowley leans into them.

And he understands the fundamental spiritual problem in a very modernist way. The problem we face is not suffering, and it’s not ethics. These are pre-modern or early modern ways of looking at the problem. No, the main problem is meaning. It’s the senselessness of the world. Crowley was motivated by this experience of senselessness at least since he was a student at Cambridge, and he writes about it at least as late as Little Essays Toward Truth.

What then determines Tiphareth, the Human Will, to aspire to comprehend Neschamah, to submit itself to the divine Will of Chiah?

Aleister Crowley, Little Essays toward Truth, “Man”

Nothing but the realisation, born sooner or later of agonising experience, that its whole relation through Ruach and Nephesch with Matter, i.e., with the Universe, is, and must be, only painful. The senselessness of the whole procedure sickens it. It begins to seek for some menstruum in which the Universe may become intelligible, useful and enjoyable. In Qabalistic language, it aspires to Neschamah.

The way he understands a possible solution to senselessness is very modernist as well. The solution cannot be sought in reason. Reason operates according to the principle of sufficient reason, i.e., for any proposition F, there must be a ground G for it, or for any event B, there must be a sufficient explanation A. Putting the principle of sufficient reason at the center of human relating to the world is what generated the picture of a senseless, purely mechanical world in the first place. Therefore, reason—specifically the application of the principle of sufficient reason—must be limited, but to limit reason it must be transcended.

But—the transcendence of reason cannot interfere with the legitimate operation of reason within its own domain. Crowley is not looking to reenchant nature in some naive way. He accepts the findings of the scientific view of reality and even holds them to be axiomatic for his spirituality. Nor can the transcendence of reason be a mere animalistic “overcoming” of reason. One cannot simply will oneself to be irrational, for instance. Both of these avenues would represent a kind of fanaticism.

So Crowley has to manuever somehow between the Scylla of rationalism on the one hand and the Charybdis of dogmatism or fanaticism on the other.

This is a very modernist—specifically German Idealist—way of looking at things. When a person with a background in the philosophy of Kant, Fichte, Hegel, and Nietzsche hears Crowley talking about transcending “because,” they’re hearing a tune they could hum in their sleep.

And Crowley’s proposed solution to this problem is will. Will transcends reason. You cannot ask “why” of will. In and of itself it prevents the questioning but instead gives orders. It’s authoritative. This is how he avoids rationalism.

But will also represents the “true” self of the individual. It is not a mere replacement for Jehovah. It is not a projection of the law of the father. Nor is it exactly bodily or animal instinct. This is how Crowley avoids fanaticism.

Babalon and the Mass

In the Gnostic Mass, the Priest takes up the role of CHAOS, who is associated with Chokmah. He serves the function of the logos or the word, which is also the phallus or the creative aspect of the Father. From his own body, he produces the seed (sperma). By means of an alchemical process, this seed will be transformed into the Mercurial Serpent, the Baphomet or Christos, the Philosopher’s Stone, etc. This product of the first operation is strongly associated with the Sun, with the path of Ayin, with Hod, but also with Kether and even the entire Tree of Life (if you draw the number 8 on it). But before diving deeper into the nature of the product, I’d like to first examine the process itself, in particular the role played by the Priestess.

If the Priest is taking up the work of CHAOS and the spiritual significance of Chokmah, then his counterpart the Priestess takes up the role of BABALON and the spiritual significance of Binah. What is her contribution, and what does that contribution imply about the nature of the God-Man produced by the operation?

In the Creed we recite, “And I believe in one Earth, the Mother of us all, and in one Womb wherein all men are begotten, and wherein they shall rest, Mystery of Mystery, in Her name BABALON.”

As compared with the treatment BABALON gets in The Vision and the Voice, this is rather terse and tends to understate her importance in the spiritual system of Thelema. But I think that has less to do with the importance of BABALON herself than the context. In The Vision and the Voice, Crowley was documenting his ascent across the Abyss to the grade of Magister Templi. There, BABALON is considered initiator. In the Gnostic Mass, by contrast, she serves as a cosmological or metaphysical principle which is relied upon in the context of a discrete alchemical operation.

This remark will make no sense to those who think the Gnostic Mass is a crossing-the-Abyss allegory culminating in the candidate (the bread particle) merging with the all-mother (the wine in the cup). But it will make perfect sense if you accept that, by at least Part VI of the Mass, the Priest is not a candidate aspiring to Binah but rather the representative of CHAOS performing a magical operation with the Priestess in her role as BABALON, with the desired effect being the production of a Divine Being at Tiphareth. In other words, the operation of the Mass is meant to move the Word down the Tree of Life from Chokmah to Tiphareth where it becomes incarnated as God Manifest. If the particle is consciousness as such, then it is consciousness-in-time (the Sun) in its finished state in the cup. But then what is it about the cup—the symbol of Our Lady—that allows this to take place?

From the article of the Creed, we find BABALON identified with Earth, Mother, and Womb. The wording suggests she is the sub-lunary context into which we are born, wherein we live, and which we eventually pass away into. In other words, she is nature.

But what is nature from a Thelemic perspective? I would like to suggest that it is neither the object studied in the field of physics, nor is it merely inert matter. Neither of these designations fits with the spiritual function of Binah, which BABALON is also associated with. The function of Binah in Kabbalah is to transform pure thinking as such (associated with Chokmah) into something like a determinate set of concepts of creation. So if we think of Chokmah as corresponding with the neoplatonic idea of nous or of pure mind, then Binah corresponds with the concept of the world-soul, nature inwardly considered as a hierarchical system of ideas or categories of existence.

Importantly, Binah represents the first point in the movement from out of Ain/Ain Soph where limitation and hence form are introduced. Ain, Ain Soph, and Kether are words for a formless All or One or None. Chokmah is this pure (N)one reflected in thinking. Binah is where differentiation is first introduced. The thought of creation (which is something like a mere urge at Kether and Chokmah) now receives articulation. It is presumably for this reason that Crowley associates Binah with the Vissudha chakra which is at the throat. It is at the throat that thoughts are articulated into speech.

So in the figure of BABALON, we see the union of the concept of nature with the concept of form or formation. While this appears to be an odd pairing, it in fact harkens back to the ancient Greek concept of nature which Aristotle articulated in the Physics, particularly in Book B.

The ancient Greek word for nature was phusis, from which we get our word physics. While we tend to think of nature as various stuff (natural things, things of nature, etc.), Aristotle said that phusis is first and foremost a principle of development (arche kineseus). The function of this principle in each natural thing (phusei onta) was to cause it to change in such a way that it comes into its end (telos). This end or finished state was understood as a particular kind of appearance (eidos) or form (morphe).

So for example, the function of the nature of an oak tree is to guide the development of an acorn into a full-grown oak by way of its intermediate stages. The nature of the oak (the image or form of the full-grown oak) serves as a kind of blueprint (paradigma) for change, so that the change is not chaotic but is rather orderly and results in the proper end (the full-grown tree). To put it another way, the nature of the tree is responsible for delivering it into its final form or appearance, which is the full expression of its being as an oak. This makes natural growth a circular process from form (implicit) to form (explicit) back to form (implicit) again in the appearance of the new acorn.

This explains why Aristotle said that the being of a natural thing is its form or appearance (morphe) and not the matter (hule) composing it. Things are intelligible to us by virtue of their ends. What differentiates an action such as running from another action such as rhetoric is the end it aims at. The same thing goes for growing things. They’re differentiated by the final form or appearance they aim at in their growth. Matter is only of secondary importance here. The delivery of the thing into its final form requires the presence of things like food, air, water, and sunlight, but these are merely enabling conditions. The essence or being of the thing is always its form or final, outward, full-grown appearance. It is that image “lurking in the background” which drives change in a particular direction and hence constitutes the characteristic movement or development of the thing which differentiates it from other things.

Incidentally, this is why Aristotle makes the rather odd proclamation that actuality precedes potentiality. On the face of it, the statement is false. It makes more sense when you realize that the word Aristotle uses for actuality (energeia or entelecheia) actually means something like “being in the work [ergon]” or “being in the end [telos],” whereas the word for potentiality—dunamis—has the connotation of matter (hule) or the workshop that something is made in where there are tools and raw materials laying around. Placing something into its end always takes priority (ontologically) over the means or circumstances under which it is done, and therefore “actuality precedes potentiality”.

Now we’re in a position to understand much better the spiritual function served by the Priestess in the Gnostic Mass—as well as “the feminine” in any magical operation.

While the Priest provides the material (hule) for the operation in the form of the seed or particle, it is the function of the Priestess to give that seed form (morphe)—to in-form it—in the “womb”. She is responsible for taking the seed and “delivering” it (like a mother or midwife) into appearance (eidos). In the context of the Mass, that which is delivered into manifestation is the God-Man, which is associated with Tiphareth, the point on the Tree of Life where God is manifest for the first time. So while the Priest is responsible for the potentiality or potency of the Christos, it is the Priestess who delivers Him into appearance or form, and therefore she is responsible for His being.

You can see this on a very concrete level in the Mass itself. The particle is crumbly. It lacks integrity. The cup has definite borders. It provides integrity.

(For that matter, compare the oaths of the Minerval and I°s, which correspond with Chokmah and Binah respectively by their chakra attributions. It’s the exact same thing, only now the candidate is the crumbly particle being supplied with integrity and therefore with the possibility of fulfilling an end.)

But by delivering the seed into manifestation, BABALON or the Priestess also delivers it to death. This is because there is no way to deliver into manifestation without also introducing becoming as a condition. A beginning (genesis) is a change from one thing into another. While things abide in beingness, they also keep changing. This change tends toward decay and ultimately death or passing back out of existence. As the German philosophers Hegel said in his Science of Logic, for finite beings “the hour of their birth is the hour of their death.” Due to the conditions that must be put into place for the introduction of something into the world, to enter the world is to immediately incur the penalty of death. This is captured in the nature of BABALON herself as feminine creator-destructor. It is also captured in the two-sided nature of the “sword” leading from Tiphareth up to Binah.

What this means is that the product of the Mass—the eucharist—has both the qualities of life and death, as these are unified in every manifest being. But it is more than this. For while Christ comes from blood and water, there is also the Holy Spirit, the third witness on Earth. This dove-serpent which deifieth man is subject to conditions of life and death. But by means of gross generation (biological reproduction), this spirit is able to utilize the process of life-death for the purpose of its own self-expression and manifestation down through the ages, thereby transcending those very same conditions. Like the example of the eidos of the oak tree moving from implicit to explicit and back again, we are witnessing here another circular process. The Holy Spirit separates from itself in its transmission, yet this separation is the very act by which it maintains its transcendental integrity. “The secret of generation is death.”

And while the blood is a reflection or image of the Father, and the water is a reflection or image of the Mother, the Holy Spirit is a reflection or image of God. It is an image or eidos which, just like the image or eidos of an oak tree, has paradigmatic power over the being it stands in relationship to. It calls it forth into its full-blown, most true configuration. While for an oak tree, that image is merely the fully grown oak, for an individual it is their true self. In other words, the serpent-Christ emerging from the Eucharistic operation is the Augoeides. By consuming the eucharist, you unite yourself with your genius or Angel. This is why Crowley says continually doing Eucharistic magic will inevitably lead toward Knowledge and Conversation.